Exploring The Met Coal Industry: Part 4

Analysis of metallurgical coal producers + unveiling a new portfolio idea

In today’s post, I am sharing my further research and thoughts on the metallurgical coal industry. This is the fourth and final part of the article series where I dive deeper into the met coal space.

In the first part, I discussed the demand and supply outlook for met coal producers, while in the second article, I delved deeper into what makes the met coal sector an interesting investment opportunity at this point in time. I would highly recommend reading the first two articles in the series if you haven’t already, as they establish the case for why the met coal industry is an attractive pond to fish in. To quickly summarize, the outlook for met coal producers over the coming decades is favorable given the limited new supply capacity expected to come online, while demand for met coal will likely grow or remain stable in the coming years, driven largely by increasing steel demand from developing countries. As for what makes met coal an interesting sector to invest in right now, the historical relationship between met coal prices at market bottoms and marginal production costs suggests we may be at or near a downturn in the met coal market.

This naturally leads to the question: ‘What is the most attractive way to invest in the met coal industry?’. In the third article, I discussed the most important criteria for comparing met coal producers. To quickly summarize, I distilled it down to four key aspects: production costs, export capacity, production mix by grade, and capital allocation.

This brings us to this fourth article, where I will evaluate US-based met coal producers to determine which company presents the most attractive way to invest in the industry.

Before diving into the analysis, let me start with brief descriptions of US-listed met coal producers. This will help set the stage for the discussion that follows in this article.

Alpha Metallurgical Resources (AMR): AMR is the largest US-based producer of met coal, accounting for c. 20% of total US met coal production. The company operates 21 mines (both surface and underground) in four regions, predominantly located in the Central Appalachian Basin. AMR’s deposits boast a mine life of 15+ years.

Arch Resources (ARCH): ARCH is a US-based coal producer focused on met coal (c. 80% of revenues), while also owning several thermal coal assets (c. 20%). The company operates seven mines in the US. Company’s key met coal assets are the underground Leer and Leer South mines located in the Northern Appalachian Basin, boasting mine lives of over 10 and 20 years, respectively. In August 2024, ARCH announced it would merge with CEIX, a largely thermal coal producer, to form a new company, Core Natural Resources (CNR). The combined company will have a portfolio of 11 mines across six states. For the purposes of this article, I will refer to ARCH as a standalone entity for a more straightforward comparison with other US-based producers.

Warrior Met Coal (HCC): HCC is a pure-play met coal producer that operates two met coal assets in the Warrior Basin in Alabama. Both assets, Mine No. 4 and Mine No. 7, are underground mines with longwall operations and estimated mine lives of over 10 years each. The company is currently in the process of developing a third asset, the nearby Blue Creek mine. With Blue Creek’s longwall operations expected to begin in 2026, the asset will boost HCC’s annual production capacity by over 50%.

Ramaco Resources (METC): METC is a met coal producer that operates deposits in the Central Appalachian region. Company’s largest asset is the Elk Creek Complex, a group of six underground and surface mines, boasting a 20+ year mine life. Aside from its core met coal business, METC owns rights to a property with an estimated presence of rare earth elements, with mineral analysis and core drilling currently ongoing. It is worth noting that METC has two share classes, with Class B shares (METCB) housing company’s royalty, infrastructure, and intellectual property assets, while the remaining assets are represented by Class A shares (METC).

Peabody Energy (BTU): BTU is a thermal and met coal producer with assets in the US and Australia. Met coal accounts for approximately 40% of company’s revenues, with met coal assets located in Queensland, Australia, and in the Warrior Basin in Alabama. Company’s key growth project, the Centurion mine in Australia, is expected to reach its full production capacity starting in 2026. Given that BTU is focused on thermal coal and its met coal assets are largely outside of the US, I will not include BTU in further discussion.

So, how do we determine which met coal producer presents the most attractive way to invest in the industry?

The best place to start is with an analysis of company valuations. After all, one producer might outperform its competitors in most evaluation criteria, but if it is trading at a much higher multiple, the market may already be pricing in the “quality” discrepancy. As shown in the table below, on a forward basis, AMR, ARCH, METC, and HCC are trading within a fairly narrow range of 7.6x to 10x EV/EBITDA. Note that the 2024E FCF is insignificant for most of these met coal producers, so it is not provided.

Now, there are several issues with this analysis that you might point out:

As you will recall from the second article, we are likely at the downturn in met coal prices, so 2024E EBITDA is not representative of companies’ normalized profitability.

Valuation based on EBITDA does not account for maintenance capital expenditures. Given that these are generally significant in the met coal industry, EBITDA does not accurately reflect companies’ cash flow generation.

So, where are the producers currently trading in terms of their normalized profitability less normalized maintenance capex? I would refer you to the table below, which includes the valuations of the met coal producers on ‘normalized EBITDA minus normalized maintenance capex.’ The table shows that all four producers are trading within a fairly narrow multiple range of 5.1x to 7.8x.

Let me quickly explain several key assumptions I am making in this estimation, namely regarding normalized met coal prices, maintenance capital expenditures, and other costs, including cash cost of sales and SG&A.

Starting with normalized realized met coal prices (see the table above), these are based on: 1) the companies’ historical average realized price discount to the Australian Coking Coal Index (see the chart below), and 2) the estimated $260/ton ($235/short ton) normalized benchmark price. To illustrate this, let’s consider the example of AMR. The company has historically realized its production at a 33% discount to the Australian Coking Coal Index (calculated quarterly). So, assuming the same discount to the $235/short ton normalized benchmark price and adding back inland transportation costs, you would arrive at an estimated normalized realized met coal price of around $190/short ton.

Moving on to maintenance capex, the estimates are based on management’s 2024 guidance. I would note that companies’ sustaining capex guidance broadly aligns with the historical sustaining capex incurred by companies on a ‘per-ton of production capacity’ basis during 2018–2023—something I consider a directionally accurate metric for through-the-cycle sustaining capex. To illustrate this, HCC’s sustaining capex has ranged from $8 to $15 per short ton during this period, with an average of $11 per short ton. Multiplying this average by company’s projected 7.7m short tons in midpoint coal production for 2024, you would arrive at c. $87m in maintenance capex, compared to management’s guidance of around $105m. Considering the inflationary pressures observed during 2018–2023, this confirms that management’s normalized capex guidance is directionally indicative of normalized sustaining capital expenditures.

As for other expenses, including cash cost of sales and SG&A, I assume they will remain in line with 2024 guidance.

I want to highlight that estimating normalized cash flow generation for met coal is, of course, an imprecise exercise. Nonetheless, I believe this analysis shows that US-based met coal producers are likely trading in a similar range on normalized cash flow generation multiples.

So, given the similar valuations across the board, which met coal producer presents the most attractive way to invest in the industry? Well, let me be upfront: Warrior Met Coal (HCC) is my pick, and I have added it to my portfolio. The rest of this article will explore the following comparison criteria to explain why I prefer HCC over its competitors as a way to play the industry:

Production costs

Export capacity

Production mix by grade

Capital allocation

Let’s tackle these in order.

Production Costs

Starting with one of the key aspects that make HCC stand out among its peer group: production costs. For a quick background, met coal production costs include direct extraction costs (i.e., mining), royalties, and transportation expenses, among other costs. In this section, I will focus on two key categories: costs before and including inland transportation.

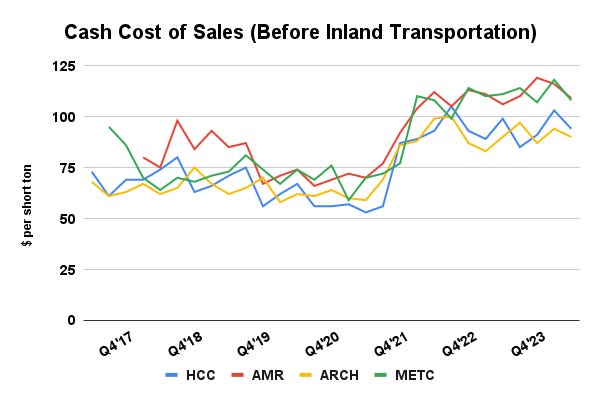

Looking at production costs before inland transportation, as shown in the table below, ARCH and HCC have generally stood out as the lowest-cost producers in recent years compared to AMR and METC. As of Q2 2024, HCC and ARCH’s pre-transportation production costs stood at $94 and $90 per short ton, respectively—about $15–$20 per short ton below the costs incurred by AMR and METC.

It is not hard to see why this is the case when you consider that the assets operated by ARCH and HCC are primarily longwall underground mines, while AMR and METC use room-and-pillar mines. For a quick recap, let me highlight that longwall operations, while requiring more upfront capital expenditures, are more efficient and cheaper than room-and-pillar mines. ARCH’s assets are primarily underground longwall-operated mines (about 80% of company’s total met coal output comes from longwall operations). The same can be said of HCC—its two operating met coal underground mines rely primarily on longwall operations. This contrasts with METC and AMR, which operate predominantly lower-efficiency and more expensive room-and-pillar underground mines. I would refer you to the 10-Ks of METC (here, p. 31, 62) and AMR (here, p. 10), which indicate that these companies do not employ longwall mining.

Now, you might be thinking, “But why do ARCH and HCC use the longwall method while AMR and METC do not?” The key aspect here is that the assets of ARCH and HCC are primarily located in the Northern Appalachian and Warrior Basins. These basins generally boast thicker, more uniform, and continuous coal seams. This makes longwall mining more efficient in these conditions, as it requires long, straight coal seams to optimize production. In contrast, the coal seams in the Central Appalachian Basin, where METC and AMR’s assets are located, tend to be thinner, more fragmented, and more variable in thickness. This makes it difficult for longwall equipment to operate efficiently, making room-and-pillar mining more effective.

So, these geological differences explain the use of different mining methods, which in turn lead to different production cost profiles.

Another angle I would like to highlight is the increasing discrepancy between costs incurred during longwall and room-and-pillar mining. If you look at the chart above, you will see that prior to 2021, the cost difference had generally been smaller compared to what it has been since 2022. One explanation, which I already discussed in the third article, is the impact of labor inflation. As you will recall, labor is a much more significant factor in the room-and-pillar mining method compared to longwall mining. This is because room-and-pillar mining requires more manual labor for cutting coal, maintaining roof support, and transporting coal across smaller production units. In contrast, longwall mining is more automated, allowing for fewer workers and higher productivity. So, while I do not have a strong view on the movement in the discrepancy between costs incurred by ARCH/HCC and METC/AMR going forward, there is a reasonable chance that the gap could widen due to labor cost inflation.

Let’s now turn to inland transportation costs. Before diving into the numbers, let me start by saying that HCC has a transportation cost advantage over its competitors. Why? Well, for a quick recap, several key factors influence transportation costs:

Distance from the deposit to the shipping port.

Availability of multiple transportation alternatives (e.g., rail and barges).

Geographical proximity of a company’s assets.

HCC has a transportation cost advantage in most all of these aspects compared to its publicly listed competitors. Starting with the distance from the nearest shipping port, HCC’s mines are c. 300 miles from the port in Mobile, Alabama. Here’s how this compares to HCC’s competitors:

The distance from ARCH’s key assets, Leer and Leer South, to the Norfolk Port in Virginia is c. 350 miles.

AMR’s largest assets by production, Marfork and McClure, are located over 400 miles from the Norfolk Port.

METC’s Elk Creek is located c. 350 miles from the Norfolk Port.

As for the availability of multiple transportation alternatives, HCC boasts three methods: truck, rail, and barges. HCC’s key advantage here is the ability to ship met coal using barges, which is cheaper than both rail and truck, through the Black Warrior River. While some of AMR and ARCH’s assets also utilize these three transportation methods, I would note that the majority of AMR’s coal has been transported via the more expensive option, rail (89% of total coal shipments in 2023). ARCH has similarly indicated that it transports the majority of its production via railroad. As for METC, none of company’s major assets have access to barge transportation.

Moving on to the geographical proximity of assets, I would highlight that HCC’s assets are located within a 50-mile radius. While METC’s key assets are similarly located in close proximity, ARCH and AMR’s assets are much more scattered. To illustrate this, ARCH’s Leer and Leer South are located over 200 miles from company’s other Mountain Laurel and Beckley mines. As for AMR, company’s largest assets by production, Marfork and McClure, are over 100 miles apart.

So, these aspects explain why HCC boasts a transportation advantage over its publicly listed competitors.

Now, if you look at the transportation costs per ton (see the chart below), you will see that HCC’s inland transportation costs have actually been generally in line with those of METC, AMR, and ARCH over recent years. So, how can we reconcile this with HCC’s transportation cost advantages outlined above?

The key aspect here is that HCC exports a significantly higher portion of its production (“substantially all”) compared to about 70% for METC and AMR and about 60% for ARCH. This is important because transportation for domestic shipments is paid for by North American steel mills and is not recorded on the income statement. While inland transportation for export volumes is also pass-through (i.e., paid for by the end consumer via a higher coal price), the key difference is that it is recorded on the income statement, in both the revenue and cost lines.

To illustrate this point, let’s consider the example of METC. As shown in the chart above, METC’s transportation costs were below $10 per short ton in 2019-2020 but have since increased and are currently in line with peer levels. This gradual increase has been driven by company’s share of exports growing markedly, from c. 30% in 2019 to around 70% currently. I would refer you to the quote from METC’s Q1 2024 conference call below.

So as you know, we pay transportation costs. It's a pass-through, but you record it on the revenue and the cost line for our export business. And in the first quarter, actually, about 2/3 of our volume was export. So certainly, that's the highest portion that we've had on a percentage basis. So it was more of a mix issue, I would say, than necessarily a higher rail rate. Rail rates did go up a little bit.

The points I am trying to make here are that 1) comparing HCC and other producers' transportation costs is not an “apples-to-apples” comparison, and 2) on an export/import-adjusted basis, HCC does boast lower costs than its competing producers.

So, with an overview of pre-transportation cash costs and transportation costs, we can now turn to total production costs. As shown in the chart below, and not surprisingly, HCC is the lowest-cost producer (before adjusting for import/export mix), followed by ARCH, AMR, and METC.

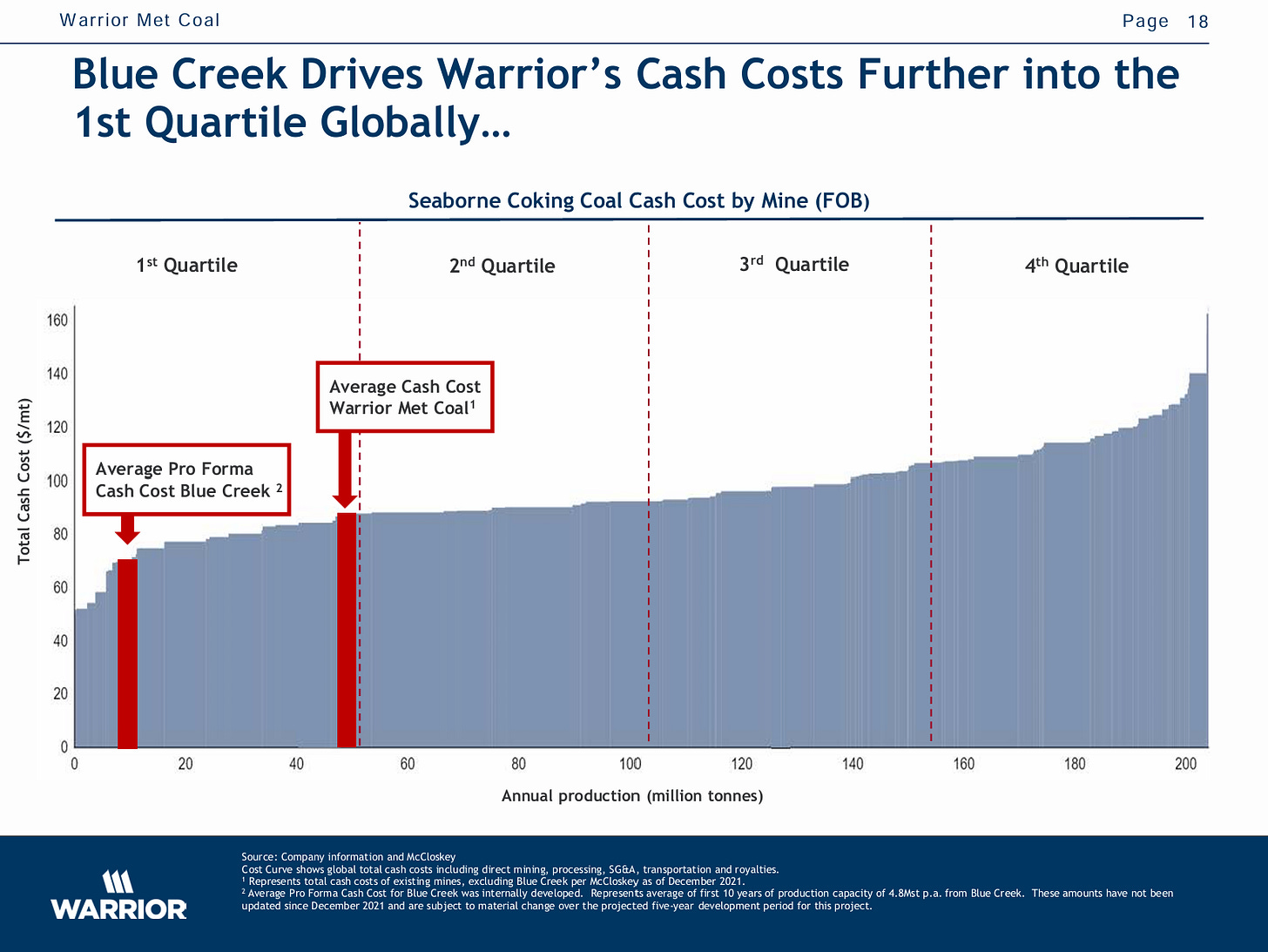

What can we expect on the production cost front going forward? Given HCC’s focus on longwall operations and transportation advantages, I expect HCC to remain the lowest-cost producer. Here, I would like to highlight the cost profile of HCC’s Blue Creek asset. As shown in the slide below, the company expects Blue Creek to boast production costs of approximately $70 per short ton, meaning that the asset will be one of the world’s lowest-cost met coal assets. I should note that this estimate from 2021 is likely too low given the subsequent cost inflation—management has recently indicated that Blue Creek costs will likely be around $90 to $95 per short ton when adjusted for inflation since 2021. Nonetheless, it is safe to assume that the asset, once fully operational in 2026, will lower company’s production costs.

What about the go-forward cost profiles of other producers? Well, AMR’s production is not expected to grow materially in the coming years, so it is reasonable to expect its cost profile to remain similar. Meanwhile, METC expects production to grow significantly over the medium term (see below), driven largely by existing asset expansions. Given that the assets operated by the company are predominantly room-and-pillar mines located in the Central Appalachian region, the capacity expansions are unlikely to significantly lower METC’s production costs.

As for ARCH, the second-lowest-cost producer, I would note that company’s transportation costs have been elevated recently due to the Baltimore bridge collapse earlier this year (see the quote from ARCH's Q2’24 conference call below; the bridge is not expected to be rebuilt until 2028). This is a tailwind that I would expect to normalize in the coming quarters and years as coal shipments continue to be redirected (i.e., new contracts with railroads are signed). Here, I would also highlight the recent merger between ARCH and CEIX. Given CEIX’s reputation as a low-cost operator with a track record of running longwall operations, it would not be surprising to see ARCH's assets’ production costs come down once the merger is completed.

Obviously, the second quarter was impacted significantly with what happened at the Port of Baltimore and the bridge collapse. And as a reminder, 50% of our metallurgical exports go under that bridge on an annual basis. So the logistics team did a fantastic job of managing that. We talked through the impact of the reduced margins there. There was a component of us having to redirect a lot of rail transportation. It was a longer transport to our DTA facility as a result. So there's rail surcharge impacts, but the team did a fantastic job of working to get that coal flow redirected.

So, overall, I think it is reasonable to conclude that HCC will likely remain the lowest-cost producer, with ARCH as the second player in this regard, followed by METC and AMR. The implications of this are significant. As discussed in the previous article, the most favorable production cost profile will make HCC and ARCH best positioned to maintain profitability and higher margins through the cycle. Another aspect is that the lowest-cost producers will remain more competitive in export markets. As you will recall from the previous article, the export markets are becoming increasingly important for US-based producers, given the prevalence of steelmaking using EAFs in the US, while the majority of new steelmaking production capacity in Asia will be comprised of traditional blast furnaces.

Export Capacity

Let’s now turn to another criterion: export capacity. Let me remind you that I am using the term “export capacity” as an umbrella for a number of interrelated factors, including access to and/or ownership of export terminals, a company’s scale, and international sales contacts, among others.

Among these, I would highlight access to and ownership of terminals as one of the key and most tangible aspects. Why? As discussed in the previous part, owning a terminal goes a long way toward optimizing logistics, storage, and shipping times. Moreover, ownership or control of an export terminal provides met coal producers with an advantage in negotiations with buyers, especially in the event of supply chain disruptions elsewhere. Another aspect is that scale, sales contacts, and access to terminals allow producers to opportunistically take advantage of price differentials between domestic and international markets.

Here’s how US-based met coal producers stack up with respect to access to and/or ownership of export terminals:

AMR owns a 65% stake in the Dominion Terminal Associates (DTA) export terminal in Norfolk, Virginia. DTA boasts a total export capacity of 22m tons annually (vs. AMR’s production of c. 17m tons). Aside from DTA, the company exports its production through the nearby Pier 6 shipping port (with a production capacity of 48m tons, including thermal coal).

ARCH (9m annual production capacity) owns the remaining 35% stake in the Dominion Terminal Associates export terminal in Norfolk. Aside from DTA, ARCH also exports its production through the Curtis Bay terminal in Baltimore, Maryland (with a capacity of 14m tons).

HCC has a long-term agreement with the McDuffie terminal in the port of Mobile, Alabama. As of 2020, the agreement was signed through July 2026 for up to 8m metric tons annually “at very competitive rates” for HCC. Company’s annual met coal production has stood at approximately 8m short tons compared to the McDuffie Coal Terminal’s total capacity of 27m metric tons.

As for METC, while limited information is available, the company does not hold ownership stakes in any export terminals. METC has outlined that some of its production is “sometimes funded through take-or-pay agreements,” implying that the company has signed long-term agreements with East Coast export terminals, namely those located in Norfolk and Baltimore.

So, what is the key takeaway here? I would note that AMR and ARCH’s production volumes cannot be exported solely through their jointly owned DTA terminal given its limited capacity (22m tons vs. production capacities of 17m and 9m tons for AMR and ARCH, respectively). This means that some of ARCH and AMR’s production must be shipped through other Baltimore/Norfolk terminals where the companies do not have ownership stakes. Nonetheless, DTA terminal ownership gives these producers an advantage in terms of export capacity over HCC and METC. I would rank HCC behind these two players, given its existing agreement with the terminal in the port of Mobile. As for METC, while limited information is available, the take-or-pay agreements seem to indicate that the contracts might not be signed on as favorable terms (in terms of both rates and capacity) as those of HCC. As an indication of this, I would again highlight the fact that during the 2022 met coal market peak, METC was unable to capitalize on higher export vs. domestic met coal prices, unlike ARCH, AMR, and HCC. This is illustrated in the chart below, which highlights that METC’s price realizations, while generally similar to competitors, lagged behind those of its peers in H1’22. This, coupled with METC being by far the smallest producer by a wide margin among the four met coal producers, implies that METC might reasonably be considered to be at a disadvantage relative to its peers in terms of what I refer to as export capacity.

Now, when reading the comparison above, one thought might have crossed your mind: “But HCC’s agreement with the port is only until 2026, so there’s a risk of the agreement being renewed at less favorable terms.” While there is no guarantee, I think that renewal at favorable terms is highly likely. HCC is the largest coal producer exporting through the McDuffie Terminal, with limited competition from other coal producers in the region. To illustrate this point, I would refer you to this table showing that total coal exports from the Mobile Port in Alabama stood at 6.3m short tons in H1’24 (5.4m in H1’23). Given that HCC’s exports were c. 4m in H1’24, you can easily see that the McDuffie Terminal was largely utilized by HCC. This, coupled with the fact that a significant portion of McDuffie’s total capacity (27m tons annually) remains unutilized, suggests that contract renewal at similarly favorable terms is likely.

So, while I think that HCC is at a slightly disadvantaged position relative to ARCH and AMR due to a lack of ownership of the terminal, the favorable geographical location of HCC’s assets relative to the port puts the company in a solid position to secure agreements at favorable terms with the McDuffie Terminal.

Production Mix By Grade

Let’s proceed to what I consider one of the key aspects: production mix by grade. For a quick background, met coal is generally differentiated by its volatile matter content, which refers to gases other than carbon that are released during the combustion process. Met coal with lower volatile content is regarded as higher quality, as it boasts a higher carbon content, meaning that low-volatility coal produces more coke per ton of feedstock. The following grades are recognized from highest to lowest quality: low-vol, med-vol, high-vol A, and high-vol B.

Production mix by grade is one of the key criteria that differentiate HCC from its competitors. As shown in the table below, HCC has boasted by far the largest proportion of the highest-quality low-volatility coal in its production mix, at 70% in 2023. METC and AMR have 21% and 23% shares in the mix, while ARCH’s primary product is HVA coal.

The reason behind these differences is that HCC operates deposits in the LV coal-rich Warrior Basin in Alabama. This contrasts with the remaining three producers operating in the Northern and Central Appalachian regions, where LV coal is generally less prevalent, at the expense of the more commonly found HVA and HVB coal grades.

To illustrate this point, I would refer you to the chart below, which displays the highest-quality met coal deposits in the US, China, and Australia. You can easily see that HCC’s assets are among only a handful of low-volatility coal assets in the US, with the remaining LV coal mines being Pinnacle (operated by Cleveland-Cliffs), Oak Grove (Crimson Oak Grove Resources), Buchanan (ASX-listed Coronado Global Resources), Shoal Creek (operated by BTU), and Kepler (operated by AMR). I would note that only three of these mines—Pinnacle, Oak Grove, and Kepler—are located in the Appalachian region, while Oak Grove, Shoal Creek, and two of HCC’s assets are in the Warrior Basin. Given that the Appalachian Basin is much larger in terms of met coal reserves compared to the Warrior Basin, this directionally illustrates that LV coal is proportionally more prevalent in the Warrior Basin than in the Appalachian.

The differences in production mix are clearly reflected in the average prices realized by the producers. As shown in the realized price chart above, HCC’s average realized price has generally been higher than those of its competitors, with an average premium of 21%, 24%, and 30% against AMR, ARCH, and METC, respectively.

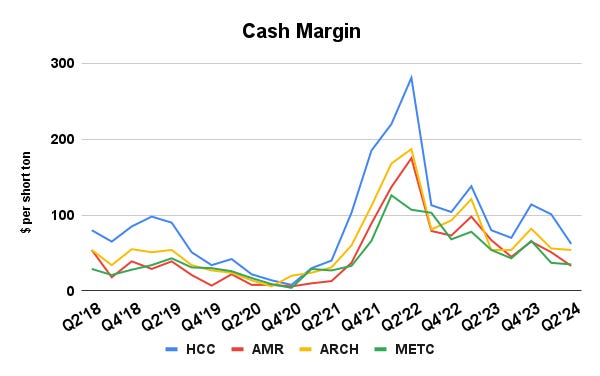

The implications of realizing higher prices are significant. Producers with higher realized prices have a greater chance of maintaining profitability through the cycle. As an illustration, I would refer you to the chart below, which shows that, driven by both higher realized prices and generally lower production costs, HCC’s historical cash margins have been markedly higher than those of its competitors during 2018-2024. Another aspect that makes exposure to LV coal important is the potentially widening spread between LV and HVA coal, as discussed in the previous article. Considering the increasing number of HVA coal-focused assets coming online in the US, coupled with limited LV coal supply globally, I would expect to see an increasing dispersion between LV and HVA prices. I would note that this is likely to be a headwind for ARCH in particular, given its focus on HVA coal.

Now, I must highlight that HCC expects its share of LV coal in production to decline markedly as the HVA-focused Blue Creek project reaches full capacity. The company has guided for a LV coal production mix share of 39% in 2027, with the rest of the production composed of HVA coal (see the slide below). This implies that HCC’s realized prices and, thus, margins might be likely to normalize closer to peer levels going forward.

The logical question, then, is, “How will the production profiles of HCC’s peers look going forward?” AMR and ARCH are likely to boast similar production mixes as they currently do, given the lack of significant new met coal capacity coming online (excluding the impact of the merger with CEIX on ARCH’s production profile). METC, nonetheless, has guided for a substantial increase in the share of low-volatility coal, driven by the expansion of company’s existing assets in the Appalachian region (see the slide below). So, if these management team projections are accurate, one could state that HCC will eventually no longer have the advantage of having the highest share of LV coal in its production mix among the peer group.

However, I would note that, until the longwall operations at Blue Creek commence, HCC’s production will remain largely focused on LV coal, allowing the company to benefit from higher realized prices in the coming years. Another aspect is that even after Blue Creek reaches full production capacity, likely in 2027, the company will still boast a significantly higher share of LV production compared to AMR and ARCH, while having a relatively insignificantly lower mix compared to METC. So, considering these aspects, I expect HCC to continue benefiting from high realized prices compared to its peers in the medium-term.

Capital Allocation

Moving on to the final criteria for comparing met coal producers: capital allocation. As discussed in the previous article, capital allocation is a crucial aspect when comparing met coal producers, given that they are mostly highly cash-generative companies (through the cycle) operating in a commodity industry with generally limited reinvestment options (into existing assets).

Historical capital returns for met coal producers, including dividends and stock buybacks, as a percentage of both 1) current market cap and 2) annual FCF for the period from 2018 to 2023 are shown in the charts below. What are the key takeaways? While all four met coal producers have generally returned a significant portion of cash flows to equity holders, we can differentiate AMR and ARCH as the companies that have initiated more sizable capital returns in relative terms over recent years. In contrast, HCC and METC have been returning noticeably lower capital in the form of dividends or share buybacks since 2020.

Given the significant difference in capital returned to equity holders between AMR/ARCH and METC/HCC since 2021, one could conclude that the management teams at AMR and ARCH have more shareholder-friendly capital allocation policies than those at HCC and METC.

But why do these differences exist, and do they suggest that HCC and METC’s capital allocation is inferior to that of their competitors? I would point out that this difference primarily reflects different capital allocation priorities rather than a reluctance on the part of management teams to return capital to equity holders. METC and HCC have been undergoing significant capital expenditures over the past few years, which has hindered their ability to return cash. METC’s capex jumped to $123m and $83m in 2022 and 2023 from sub-$50m levels in 2018-2020 as part of its existing asset expansion program. As for HCC, due to company's investments in the Blue Creek asset, capex rose significantly to $492m compared to sub-$200m levels in previous years. I would highlight that, given ESG concerns, met coal producers have been facing increasing difficulty in receiving financing, which explains why companies are primarily using internally generated cash flows for new/existing asset development capex and/or capital returns.

With growth capex fading in the coming years, I would expect HCC to initiate sizable capital returns more in line with those of AMR and ARCH. As an illustration of the management team's willingness to return cash, let me note that during 2018–2019, HCC returned c. 60–90% of annual FCF as capital returns (primarily via special dividends). As for METC, the company historically did not generate positive free cash flows until 2022, limiting its ability to return cash. However, considering that the company has returned c. 40% of its FCF over the last two years to equity holders, I would similarly expect sizable capital returns going forward.

Another angle here is that investments in growth projects might increase HCC and METC’s cash flow generation and, thus, capital returns to equity holders. While I am not sure if production capacity expansions will ultimately prove to be more value-accretive than stock buybacks, I would note that investments in growth are strategic, given the limited number of growth projects and expansions coming online in the US. Additionally, given the projected high returns on investment (e.g., HCC expects a 27% IRR from Blue Creek at a $150/ton met coal price), the growth projects might potentially be more value-accretive down the road. Again, this is uncertain, but the point I am trying to make is that HCC, AMR, ARCH, and METC have all similarly displayed solid capital allocation when accounting for their different cash flow generation profiles and capital allocation priorities.

Conclusion

This article caps off my four-part series covering the met coal industry. My analysis of the US-based met coal producers on key criteria indicates that HCC is the most attractive way to play the sector. HCC has the lowest cost structure and boasts the highest share of low-volatility coal in its production mix. On top of that, the company is currently in the process of developing Blue Creek, one of the few met coal assets coming online in the US. The project, once fully operational, will significantly boost company's production and may potentially lead to higher capital returns down the line. Given these aspects, coupled with relatively insignificant valuation differences between the four US-based producers, I have added HCC to my portfolio.

HCC without terminal ownership could be a long-term issue. There's been a severe lack of capex there in recent years, with accompanying frequent equipment failures and capacity issues. Mcduffie is investing some money into the port to help rectify this, while simultaneously reclaiming a portion that used to be for coal to transition it to container. I think this shows where their priorities are, and that there's a risk that more of the coal terminal is reclaimed and transitioned to container or auto (now a big business in Alabama) in the future.

Mcduffie is a state asset, and while they do work with and price favorably for HCC, this lack of control and reliance on the state for capex and terminal management puts them at a disadvantage compared to the other terminals. There's also not really an easy second option, New Orleans is the secondary port, and transport costs there are much more expensive.

Agree that HCC is still an incredible company, and that Blue Creek will be a world class asset. However, capital allocation differences are stark. HCC does not see value in buybacks (even after the comparative outperformance of their peers that do). The CFO told me to the nodding approval of the CEO that 'we don't do buybacks here, we buy real assets'. Expect them to either buy assets or give back capital in the form of dividends. I know there's been some hope that post Blue Creek they focus on buybacks, but from a cultural perspective from everyone in management I've spoken to, that's not the plan.

Thanks for the great article. Really enjoyed the series!