Exploring The Met Coal Industry: Part 3

A framework for comparing metallurgical coal producers

In this post, I am back with further research and thoughts on the met coal industry. This article marks the third part of a multi-post series covering the sector.

In the first article, I discussed the outlook for met coal producers, while in the second, I delved deeper into what makes met coal producers an interesting investment opportunity at this time. To quickly summarize, the outlook for met coal producers over the coming decades is favorable. New supply capacity is expected to be limited, while demand for met coal will likely grow or remain stable in the coming years. Meanwhile, electric arc furnaces are unlikely to replace traditional blast furnaces in the near future, as most new steel production capacity in key steel-producing countries will consist of blast furnaces. As for why met coal is an interesting sector to invest in right now, the historical relationship between met coal prices at market bottoms and marginal production costs suggests we may be at or near a downturn in the met coal market.

This brings us to the question: What is the most attractive way to invest in the met coal industry? To answer this, we need to identify the key criteria for assessing met coal producers and then analyze the industry players accordingly. Given how lengthy this discussion will be, I have decided to split the third part into two separate posts. This article will outline the general criteria and framework for evaluating different met coal producers, while the upcoming post will present an analysis of US-listed met coal producers based on these criteria.

So, what are the key criteria for comparing different met coal producers as investment opportunities? For many value investors, "valuation" would likely be one of the first answers. This is not surprising—valuation is indeed a key factor in stock selection. However, if you look at the valuations of US-listed producers, you’ll see that most of them are trading at fairly comparable multiples. For instance, I could point to ARCH, METC, HCC, and AMR, all trading at around 4x TTM EBITDA. On a forward EBITDA basis, the multiples are a bit more varied but still fall within a relatively tight 7x-8.5x range.

So, how do we decide which met coal producers present the most compelling valuation? Well, there are several aspects I believe are worth assessing when evaluating met coal producers:

Production costs

Export capacity

Production mix by grade

Capital allocation

In this article, I will explore these aspects in more detail, with specific examples involving US-based met coal producers.

Let’s dive right in.

Production Costs

Starting with what I consider one of the key aspects: production costs. For a quick background, met coal production costs comprise direct extraction costs (i.e., mining), royalties (payable to landowners and/or the government for the right to extract resources), and transportation expenses, among other costs. This section will focus on the two key buckets that are most important: extraction costs and transportation expenses.

What determines these costs for different producers? As for extraction costs, these depend on the method used to extract coal. The two primary methods are surface and underground mining. Surface mines are typically more efficient and cheaper to exploit compared to underground mining. Delving a bit deeper, let me note that both surface and underground mines have different sub-methods.

For surface mines, there are two methods: 1) dragline and 2) shovel and truck. The dragline method involves an excavator moving a bucket attached to a long boom toward itself across the ground. Meanwhile, the shovel and truck method is a more precise digging technique, where an excavator digs into the ground and loads the material directly into trucks.

As for underground mining, the two key methods are longwall and room-and-pillar mining. The longwall method uses a shearer that moves along a coal face to cut coal. In contrast, room-and-pillar mining involves mining coal in a series of parallel “rooms,” leaving pillars of coal to support the roof.

Without going into too much detail, I will note that dragline mining is cheaper and more efficient than the shovel and truck method. Similarly, longwall mining is more efficient than room-and-pillar mining, although it requires higher upfront capital expenditures.

To illustrate the difference in costs incurred due to different mining methods, let’s consider two US-based met coal producers: METC and ARCH. If you look at the 2024 cash cost guidance of both companies, ARCH has guided for cash costs of $87-$92 per short ton, while METC expects to incur pre-transportation cash costs of $105-$111 per short ton. Why the difference?

To understand this, let’s look at the deposits operated by the two companies. Starting with METC, company’s key asset is the Elk Creek Complex (64% of the company’s total production by volume in 2023), located in the Appalachian Basin. The Elk Creek Complex is primarily an underground mine, consisting of 4 underground and 2 surface mines, with the underground mines employing the room-and-pillar method.

As for ARCH, company’s key assets are the Leer and Leer South mines in the Appalachian Basin (75% of the company’s met coal production by volume in 2023). While Leer and Leer South employ both longwall and room-and-pillar methods, they are mined primarily using the longwall operations. I would refer you to the slide from ARCH, which indicates that the company generates about 80% of its coking coal output from longwall operations.

So, given that longwall operations are more efficient and cheaper than room-and-pillar mining, it’s clear why ARCH’s production costs are lower than those of METC.

Now, this comparison isn’t perfect, given that 1) METC’s Elk Creek Complex includes two surface mines, and 2) the companies’ cost guidance also incorporates other, smaller assets. Nonetheless, it’s reasonable to conclude that different mining methods largely explain the difference between METC and ARCH’s guided production (pre-transportation) costs.

I would quickly note that the cost difference between underground longwall and room-and-pillar methods has been increasing in recent years. If you look at METC and ARCH’s costs incurred right before COVID, in Q4’19, the difference was a meager $4/short ton ($70/short ton for ARCH compared to $74/short ton for METC). One explanation for this is that labor is a much more significant factor in the room-and-pillar mining method compared to longwall mining. This is because room-and-pillar mining requires more manual labor for cutting coal, maintaining roof support, and transporting coal across smaller production units. In contrast, longwall mining is more automated, allowing for fewer workers and higher productivity. Given the significant labor cost inflation in recent years, this helps explain the increasing discrepancy between ARCH and METC’s extraction costs. While I have no strong view on labor inflation in the coming years, I point this out to highlight that met coal producers with room-and-pillar operations might be more susceptible to cost inflation during both inflationary and disinflationary/deflationary periods (due to wages being sticky).

Now, let’s turn to the other key cost: transportation. Let me clarify that here I am referring to the cost of transporting met coal from the mine to the port (i.e., inland transportation), from where it is subsequently exported to the seaborne market. Transportation costs are a significant part of the cost structure, given that 1) met coal is heavy on a per-ton basis compared to other commodities, and 2) met coal deposits are often located in remote areas far from steel mills.

Several key factors influence transportation costs:

Distance from the deposit to the shipping port.

Availability of multiple transportation alternatives (e.g., rail and barges).

Geographical proximity of a company’s assets.

While the first aspect is obvious, the second—multiple transportation alternatives—allows the met coal producer to have more bargaining power with the rail operator. Moreover, a producer with multiple alternatives can opportunistically shift between different transportation methods when their prices become more favorable. As for geographical proximity, this generally allows a company to ship larger volumes using a single logistics network, enabling it to take advantage of economies of scale.

An example will best illustrate the key drivers behind transportation costs. Let’s consider two of the largest US met coal producers: HCC and ARCH. Here’s how their transportation expenses looked in the most recent quarter:

ARCH’s transportation expenses were $42 per short ton.

HCC lumps transportation costs together with royalties. Nonetheless, judging by the average royalties paid over the last three years, the inland transportation costs stood at around $30 per short ton.

Several factors explain this difference:

HCC’s mines in Alabama are about 300 miles from the closest port in Mobile, Alabama, compared to about 350 miles from ARCH’s key Leer and Leer South mines in Virginia.

HCC’s mines are in closer geographical proximity, within a <50km radius, compared to ARCH’s more scattered assets. Leer and Leer South are much farther from ARCH’s other coking coal assets in the Appalachian region. For example, there is a 200-250 mile distance between Leer South and ARCH’s Mountain Laurel and Beckley mines.

So, these factors explain why HCC benefits from more favorable transportation costs compared to ARCH.

Why are production costs important? Well, a better cost profile increases a US met coal producer's chances of remaining profitable through the cycle. As discussed in my previous article, while we may currently be at downcycle levels, there is still a risk of further short-term met coal price declines, particularly given the weakening steel demand in China. Since most US met coal producers are currently operating at break-even levels, a further price decline could lead to operating losses. So, having a lower cost structure is crucial for avoiding potential production cuts if prices fall further.

Another angle is that lower production costs allow met coal producers to be more competitive in export markets. To elaborate, let’s backtrack a bit. As mentioned in the first article, developed economies, primarily the US and Europe, are increasingly transitioning to steel production with electric arc furnaces. As an illustration, these now account for over 70% of steel production in the US. Combined with ESG trends, this suggests that domestic and European demand for met coal can reasonably be expected to decline in the coming years. The key implication, then, is that U.S. producers will likely export an even higher percentage of their production (c. 70% of domestic production is currently exported). The key end markets are and will remain more distant Asian markets, where traditional blast furnaces will continue to dominate steel production.

Now, US producers largely compete with Australian peers met coal in export markets. While production costs for US and Australian producers are broadly similar, Australian producers benefit from significantly lower freight costs to Asian markets (about a $25/ton difference as of March, as shown in the chart below). This means that US-based producers would need to sell comparable-quality met coal at a discount to Australian exports to remain competitive.

To illustrate, let’s consider METC. Adding the company’s 2024E cash cost guidance midpoint of $108/short ton to an estimated $26/short ton in inland transportation (in line with Q2’24), you arrive at $134/short ton, or $150/ton in production costs before freight. Assuming a similar production cost profile for a competing Australian producer, METC would need to sell its met coal at a discount equal to the freight differential (let’s assume $25/ton). Using the current price of around $200/ton for East Coast HVA coal as a proxy for METC’s realized prices, this would mean company’s margins would drop significantly, from $50/ton to $25/ton. While this example isn’t precise, it directionally highlights the importance of a lower cost structure for competitiveness in export markets.

Export Capacity

Let’s now move on to another important aspect: export capacity. Here, I use the term "export capacity" as an umbrella for a variety of interrelated factors, including access to and/or ownership of export terminals, a company’s scale and international sales contacts, among others.

Given the discussion in the previous section about the importance of exports, it is clear why export markets are crucial for US-based met coal producers. In this context, it’s easy to see the role played by what I refer to as "export capacity." Among the reasons, I would first highlight that export terminals are often bottlenecks in the supply chain, so owning a terminal goes a long way toward optimizing logistics, storage, and shipping times. Moreover, ownership or control of an export terminal provides met coal producers with an advantage in negotiations with buyers, especially in the event of supply chain disruptions elsewhere. Another aspect is that scale, sales contacts, and access to terminals allow producers to opportunistically take advantage of price differentials between domestic and international markets. To explain this point, let me note that domestic met coal contracts are generally agreed upon at a fixed price, while export contracts are typically priced in line with a met coal index. So, larger producers with access to terminals and sales contacts have the optionality to ramp up their production and/or resell other domestic producers’ coal in the export markets during spikes in international met coal prices.

Let me provide an example demonstrating the importance of ‘export capacity’ by contrasting two US-based met coal producers: AMR and METC. Starting with AMR, the company is the largest met coal producer in the US that owns a majority stake in the Dominion Terminal Associates, a coal export terminal in Newport News, Virginia. Among other benefits, majority ownership of the terminal allows AMR to resell other domestic production into the seaborne met coal market when seaborne prices spike above domestic price levels. For instance, last year, AMR purchased coal from other domestic met coal producers (who lacked access to terminals and similar international sales contacts) and subsequently exported it, capitalizing on higher international met coal prices relative to domestic prices (see the quotes from AMR’s Q4’23 conference call below). This allowed the company to generate incremental revenues at essentially no cost by utilizing its ownership of the terminal and international sales network.

Export met tons priced against Atlantic indices and other pricing mechanisms in the fourth quarter realized $175.32 per ton, while export coal priced on Australian indices realized $213.41. These are compared to third quarter realizations of $136.76 per ton and $158.56, respectively.

[…]

Also, we have had opportunities to purchase a higher volume of clean coal to add to the portfolio than was budgeted.

In contrast, METC is a significantly smaller met coal producer (with an estimated 4m short tons in 2024 production compared to around 17m for ARCH) that does not own any export terminals. This limits the company’s ability to shift a larger portion of its production to export markets. For example, during the met coal market peak in mid-2022, major US-based met coal producers, unlike METC, were able to capitalize on higher export prices. To illustrate, ARCH, AMR and BTU were able to sell met coal in export markets at an average realized price of over $285/short ton in Q2’24, which was significantly higher than METC’s $215/short ton, despite broadly comparable met coal grade mixes. Another example of the importance of export capacity is that METC, lacking terminal ownership, transports a portion of its production through export terminals under take-or-pay arrangements. This means that METC is likely to export coal even if international prices are less favorable than domestic prices.

So, I think it is safe to conclude that a company’s scale, access to terminals, and sales contacts are important factors when evaluating met coal producers.

Production Mix By Grade

Let’s now turn to another criteria for comparing met coal producers, production mix by met coal grade. For a quick background, met coal is generally differentiated by its volatile matter content, which refers to gases other than carbon that are released during the combustion process. Met coal with lower volatile content is regarded as higher quality, as it boasts a higher carbon content, which means that low-volatility coal produces more coke per ton of feedstock. The following grades are recognized from highest to lowest quality: low-vol, med-vol, high-vol A, and high-vol B. In the US, LV is primarily mined in the Central Appalachian (in West Virginia) and Warrior Basins (in Alabama) while other coal grades are ample in the Central Appalachian.

Given its higher carbon content, LV met coal is generally realized at higher prices compared to other coal grades, i.e., at a smaller discount to the benchmark levels. So, having a larger exposure to higher-quality coal clearly allows a producer to maintain higher margins and thus higher profitability through the cycle. Let me again illustrate this with an example, this time using HCC and AMR. If you look at both company realized prices over the last two quarters, you will see that AMR’s realizations stood at $142 and $167 per short ton in Q2 and Q1 compared to $186 and $234 for HCC. It is easy to explain if you look at the companies’ 2023 production mixes by coal grade. As shown in the slides below, last year HCC was predominantly a producer of the highest quality premium low volatility coal (LV, 70% of production mix) compared to 15% LV coal share in the production mix for AMR.

What makes production mix by grade interesting is the potential for the LV premium over lower-quality grade coal to widen going forward. Here, I would like to briefly discuss the concept of relativities. Relativities refer to price relationships between different grades of coal used in steelmaking. As shown in the chart below, as of August, HVA coal (one of the most commonly found in the US) was trading at roughly a 5% discount to U.S. LV coal.

Now, looking at the chart above, you will notice that over recent years, the LV premium over HVA has ranged from 0% to c. 20%, driven largely by seasonal fluctuations in demand and supply for these coal grades (i.e., the premium increases in periods when demand for steel is high). Given these fluctuations, it is likely that the premium might revert to wider levels when steel demand grows. However, what’s interesting here is that there are structural reasons why the premium might increase: namely, 1) declining LV coal production globally and 2) new HVA supply coming online in the U.S. Let me unpack these points.

Starting with declining LV coal, let’s establish the fact that low-volatility coal is becoming increasingly scarce globally. A glance at the upcoming coking coal project pipeline (see here) indicates that the new supply of low-volatility coal in the coming years is minimal, with only a handful of projects expected to come online later this decade or in the 2030s. The lack of availability of LV coal has been highlighted by U.S.-based met coal producers—for example, see the quote from ARCH below. Here, I would like to quickly highlight that LV coal is critical in most coking blends and cannot be substituted by HVA or other coal grades.

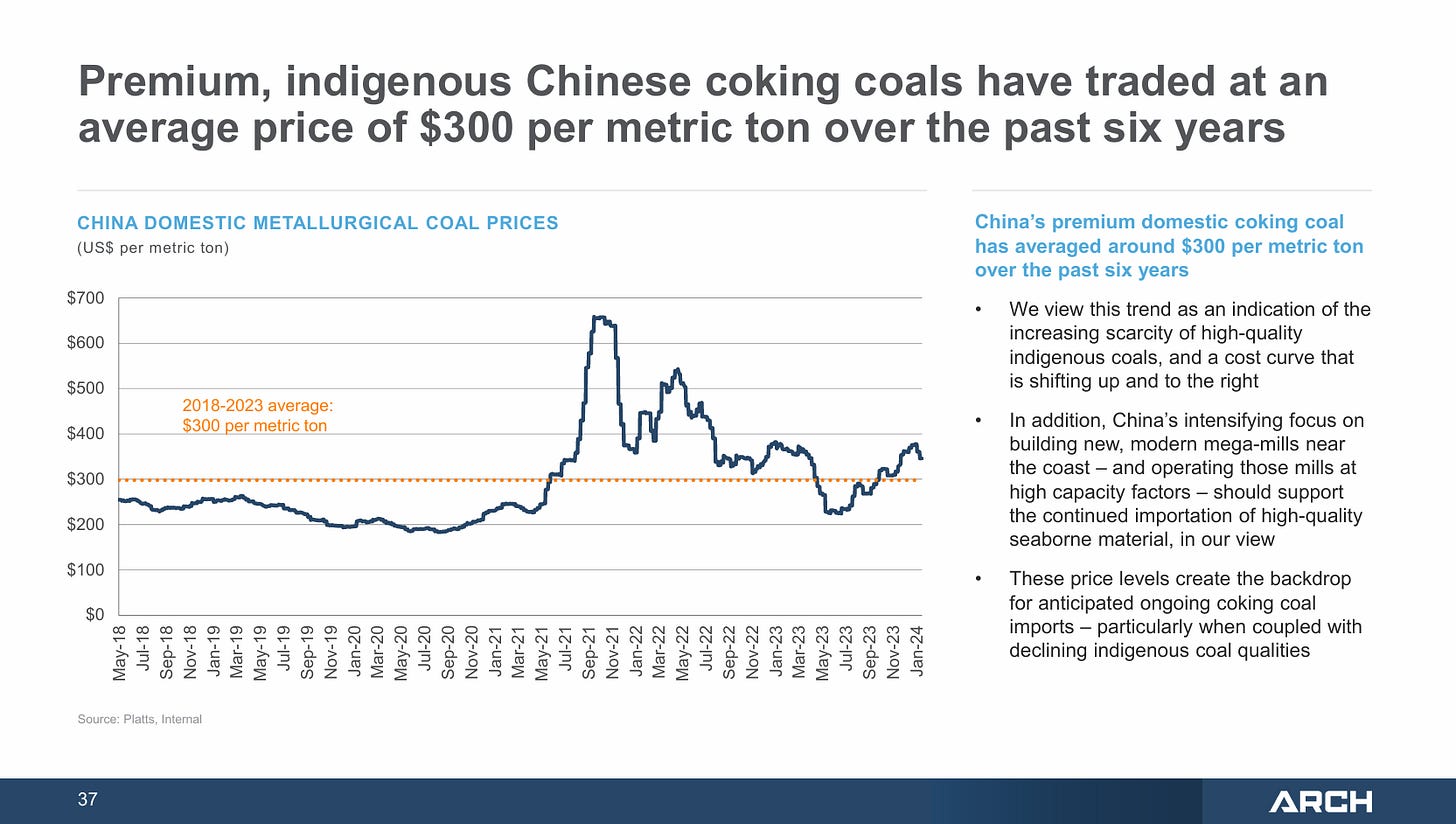

To illustrate the scarcity, let’s consider the largest met coal producer and importer, China. As discussed in this article, the production capacity of premium low volatility (PLV) coal in China has been on a downward trend in recent years, largely due to depletion of resources. No new investment in PLV mines in China is expected in 2024. Not surprisingly, then, premium domestic coking coal prices in China have, on average, been significantly above historical averages over recent years (see the slide below). Another indication of increasing LV scarcity is that China’s seaborne coking coal imports have increased over recent years despite materially higher imports from Russia and Mongolia. So, the takeaway is that we are likely to see increasing LV coal scarcity and, thus, upward price pressure in the coming years.

Yes, one of the things I would point to is, different products play different roles in coking coal blends. And so, right now, as we discussed, as Paul noted, coking coal exports out of Australia are down 40 million tons, 40 million metric tons since 2016. And we continue to see operational challenges there. So there’s real pressure on availability of premium low vol, and premium low vol does have a very specific role that it plays in blends. And so look, I think there’s scarcity there.

As for the new HVA supply in the US, I would simply point you to several new and recent HVA coal-focused projects:

HCC’s Blue Creek mine (longwall operations are expected to commence in 2026).

Allegheny Metallurgical’s new mine in West Virginia (production commenced in December 2023).

ARCH’s Leer South (production commenced in 2021; longwall expansion is ongoing).

These are sizable projects. ARCH’s Leer South production stood at 2.7m short tons in 2023, while HCC’s Blue Creek and Allegheny’s mine have annual production capacities of c. 3m and 10m short tons, respectively. This compares to 67m short tons of total metallurgical coal produced in the US in 2023 (see the chart below).

So, given these dynamics, US-based producers are likely to see an increasing dispersion between LV and HVA prices in the coming years. This indicates that met coal producers with higher exposure to LV coal will likely generate increasingly higher margins in the medium to long term, which would obviously render them more attractive compared to peers.

Capital Allocation

A discussion of the aspect above leads to the final criterion for evaluating different producers: capital allocation. Capital allocation is crucial, considering that met coal producers are mostly highly cash-generative companies (through the cycle) that operate in a commodity industry with generally limited reinvestment options (into existing assets). This makes shareholder-friendly capital allocation, including sizable dividends and stock buybacks, important for investors. After all, if a company boasts higher relative profitability but does not return capital to equity holders like its peers, it is likely to trade at a discount to its comps.

Let me again turn to several examples to illustrate the capital allocation point. Let’s consider AMR, which is often regarded as the best-managed met coal producer and has generally traded at a premium to comps. It is not hard to see why if you look at AMR’s capital returns over recent years. Since 2021, AMR has returned approximately 50% of its current market capitalization in the form of buybacks and common/special dividends, driven largely by elevated met coal prices in 2022. I would also like to highlight that in 2022, AMR became the first US-listed met coal producer to repay its debt.

I would contrast this with BTU, a thermal and met coal producer with assets in the US and Australia. The company has a history of pursuing expensive acquisitions (e.g., see here), which led to elevated debt levels prior to the 2022 thermal and met coal market peak. This has resulted in the company dedicating its cash flows generated during the market peak to debt reduction, which has limited the pace of buybacks. Since 2021, the company has returned 15% of its current market capitalization to equity holders, significantly lower than that of AMR. I would note that the comparison is not perfect, given the different production profiles—BTU generates a significant portion of its revenues from thermal coal (which was, in fact, a tailwind for BTU compared to AMR during 2022). Another aspect is that BTU has been making investments in the development of its Centurion asset located in Australia, limiting the pace of buybacks. Nonetheless, I think this example directionally shows why AMR is perceived as having more solid capital allocation. BTU’s average to subpar capital allocation is also illustrated by the recent involvement of activist Thomist Capital. In its filing, Thomist has made suggestions regarding the return of significant cash currently sitting on BTU’s balance sheet, among other recommendations.

Now, I would note that a lack of capital returns might not be negative if the management team is prioritizing growth projects. Aside from Peabody’s investment in Centurion, I could refer you to HCC’s ongoing investment in Blue Creek. As shown in the slide below, HCC expects a 2.4-year payback period with $150/ton met coal prices. While I am not sure if this target is achievable or if cost overruns are likely, the point I am trying to make is that a lack of capital returns to equity holders is not necessarily indicative of poor capital allocation.

Conclusion

This caps off the third article in the series on the met coal industry. With the criteria for evaluating met coal producers presented, I intend to return with the final article of the series, assessing US-based met coal producers, in the coming weeks.

Good article, thanks for sharing your work.

Excellent, can't wait for the next one.