In this post, I am sharing my research and thoughts on the metallurgical coal industry, as I have been taking a deeper look into the sector recently. This article marks the first part of what I intend to be a multi-post series covering the industry.

Why met coal? What piqued my interest in this space is legendary value investor Mohnish Pabrai making a significant bet on met coal producers in recent years. Since mid-2023, Pabrai has accumulated and held sizable positions in coal producers, with only a handful of met coal names comprising c. 30% of his U.S.-based portfolio. Notably, in Q2, Pabrai materially increased the stakes in his two largest met coal holdings, AMR and ARCH, with coal producers now making up about 20% of his total portfolio. Pabrai is admittedly not your typical diversified investor and is well known for making aggressive bets, so the sizing of his coal positions is not surprising. Nonetheless, given Pabrai's impressive investing track record (13x return from 2000 to 2018), I cannot help but wonder why he thinks met coal is an attractive pond to fish in.

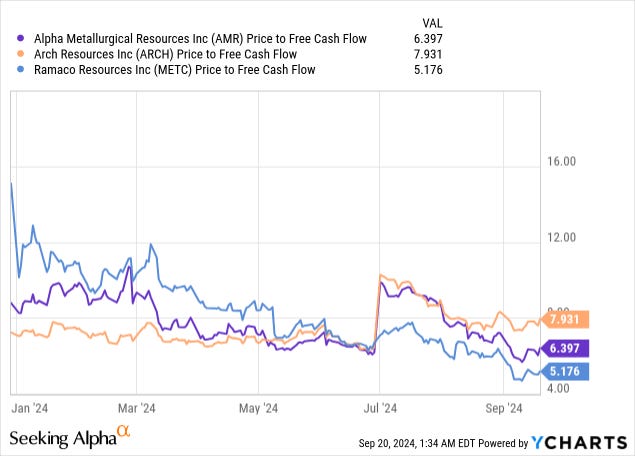

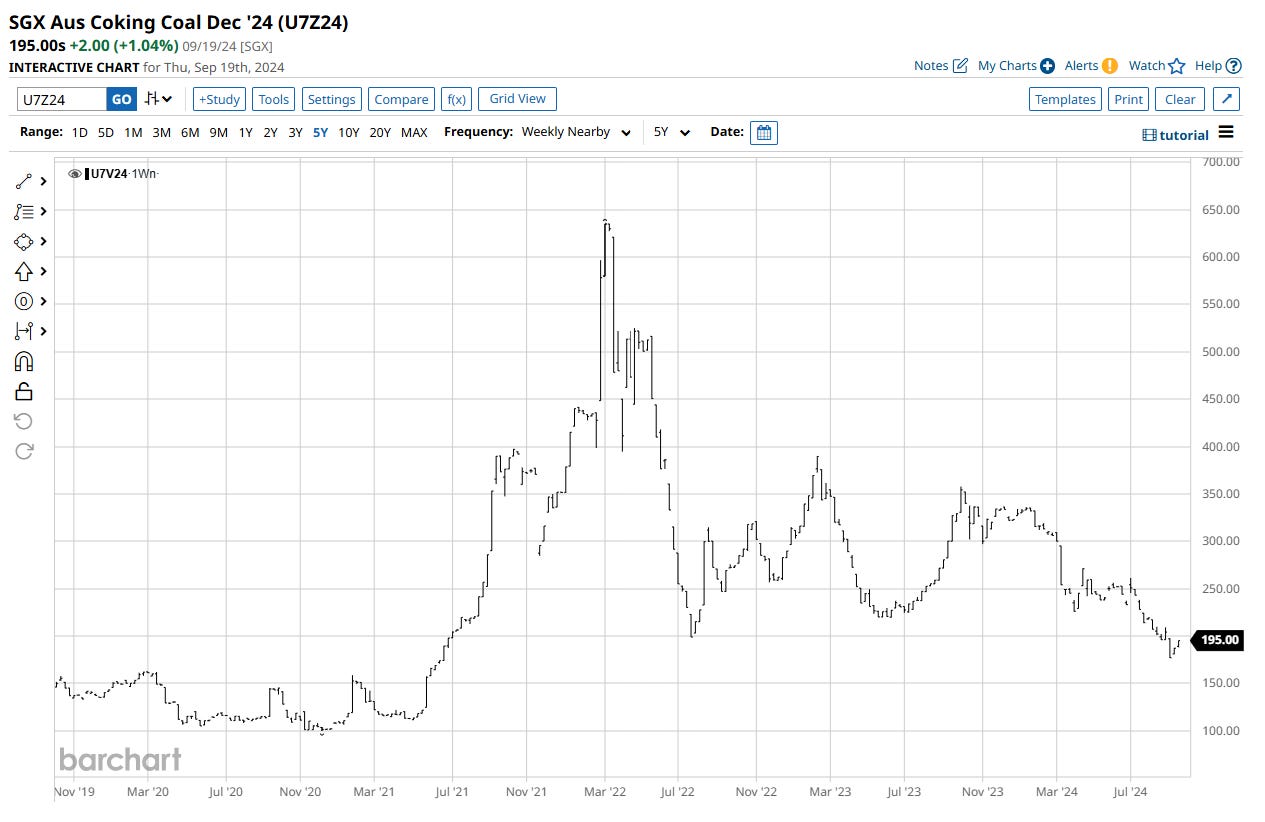

At first glance, it is not hard to see why Pabrai might find value in the met coal space. As shown in the chart below, US-listed met coal producers are currently trading at approximately 5-8x forward P/FCF multiples. Considering that met coal prices are currently hovering at multi-year lows (see another chart below) and are likely below mid-cycle levels, I would say that these valuations are quite undemanding.

You might now be thinking, “But isn’t coal a dying industry, which would suggest that these valuations are likely appropriate?” I would argue that this perspective is not entirely accurate, as it is important to differentiate between met coal (used to produce steel) and thermal coal (used to produce electricity). Consumption of thermal coal has been steadily declining in developed markets due to ESG and decarbonization trends. While developing countries, primarily China and India, have seen thermal coal consumption increase in recent years, the existence of cheaper alternatives for electricity production, including natural gas and nuclear energy, suggests a potential secular decline in thermal coal demand in the coming years.

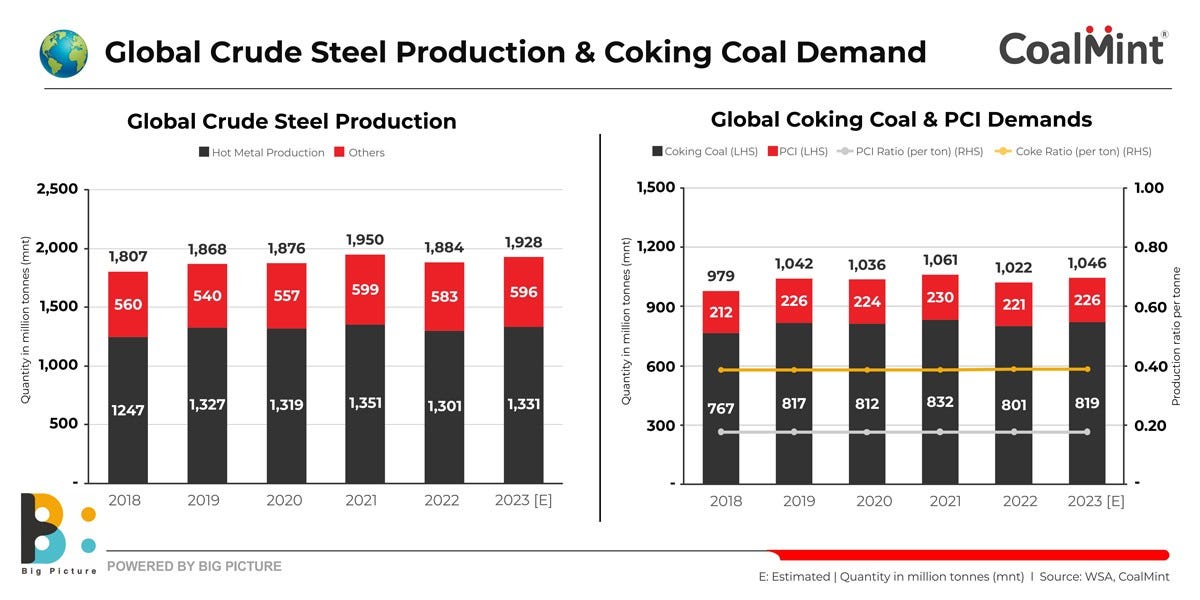

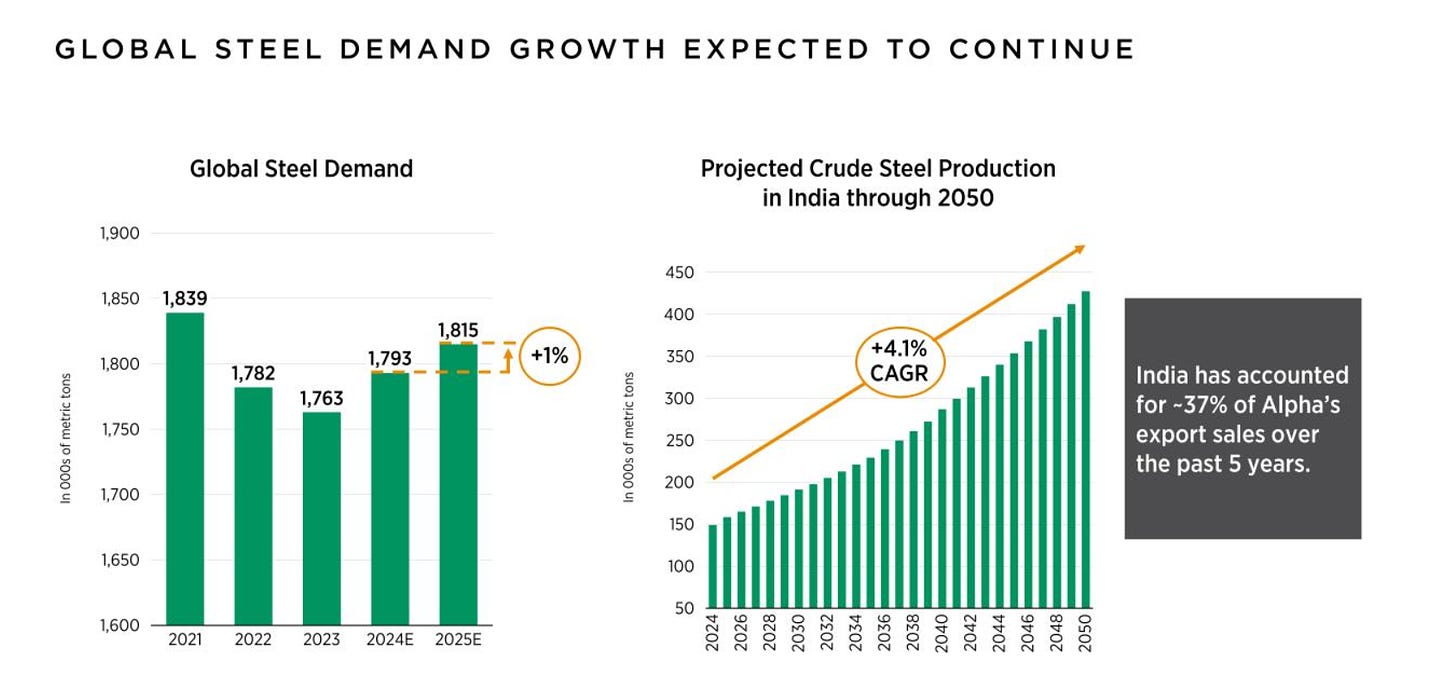

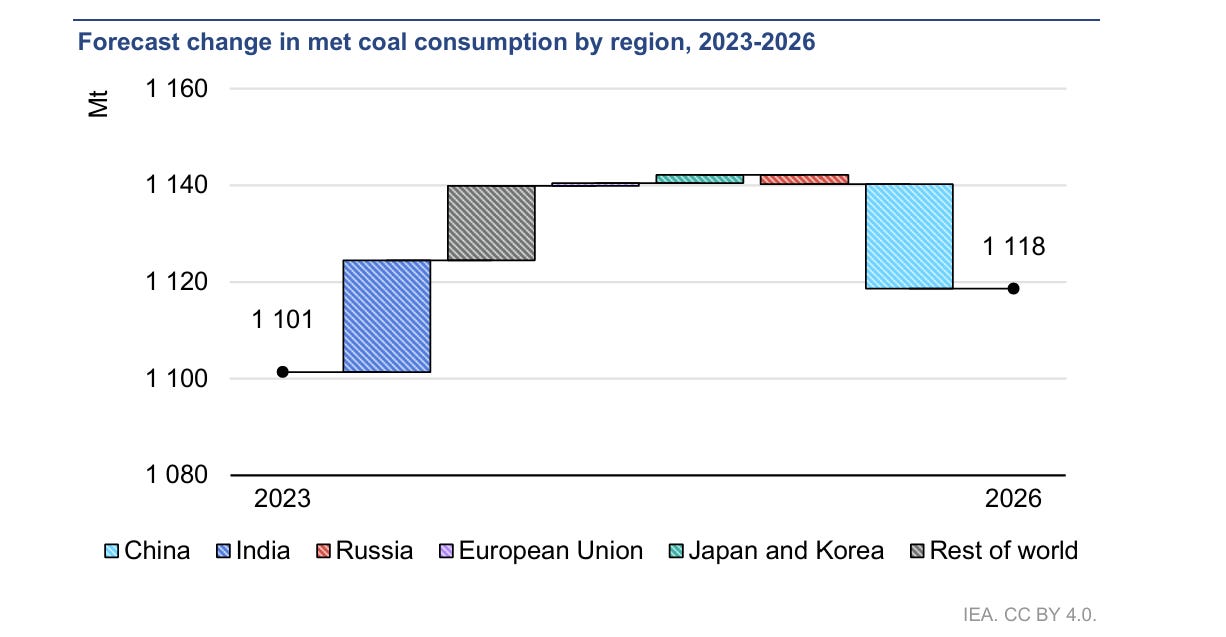

Met coal, on the other hand, seems to present a different story. A quick look at several data points, including global trade volumes (see here, p. 9) and global demand (see the chart below), indicates that met coal consumption has generally been stable or growing in recent years. Given that steel is used in various growing end-markets, including infrastructure and defense, it is reasonable to assume that these trends are likely to continue. Therefore, I would be hard-pressed to label met coal a ‘dying industry.’ Instead, met coal producers likely have a long runway for cash generation and profitability ahead of them, making the current valuation multiples undemanding.

So, these aspects prompted me to explore the met coal industry in more depth.

As for the structure of the series, this article will cover the broader outlook for met coal producers. The second part will focus on what makes met coal an interesting investment opportunity currently (i.e., why now?). The third part will delve more deeply into the key industry players to determine the most attractive way to invest in the industry. However, I should note that this structure is not fixed and may change as the series progresses.

Now, let’s dive right in.

For a quick background on the industry, metallurgical (or coking) coal is the highest calorific value and purity coal, primarily used as one of the key inputs in steel production. As part of the steelmaking process, met coal is first heated in a coking furnace (without oxygen) to create coke. The resultant coke is then mixed with iron ore in a blast furnace (along with limestone) to produce iron. Subsequently, iron is heated and refined to produce steel. Thus, it is easy to see why demand (and, consequently, the prices of met coal) are tightly correlated with the demand for steel.

Without going into too much detail regarding met coal grades, I should note that met coal is differentiated by its volatile matter content, which refers to gases other than carbon that are released during the combustion process. Met coal with lower volatile content is regarded as higher quality, as it boasts a higher carbon content. The following grades are recognized from highest to lowest quality: low-vol, med-vol, high-vol A, and high-vol B.

The largest met coal exporters are Australia (50% global market share as of 2022), followed by Russia (16%), the US (13%), and Canada (9%). The largest importers are India (21% of total imports as of 2022) and China (20%). For a more extensive background on the met coal industry, I would refer you to this recent post from Eagle Point Capital.

So, what is the bull case for met coal producers?

Well, if you are bullish on met coal, I think that your high-level investment thesis likely rests on three key points:

The supply of met coal will remain at current levels or grow only marginally in the coming years.

Global demand for steel will remain stable or grow going forward.

Met coal will retain its dominant share of steel production compared to steel production with electric arc furnaces.

In this article, I will address these points in order. Before proceeding, however, I must note that the coal market is obviously large and complex, and a full overview of the industry would likely require an entire book. What follows is a high-level summary of my research notes on the industry.

With that said, let’s dig in.

Met Coal Supply

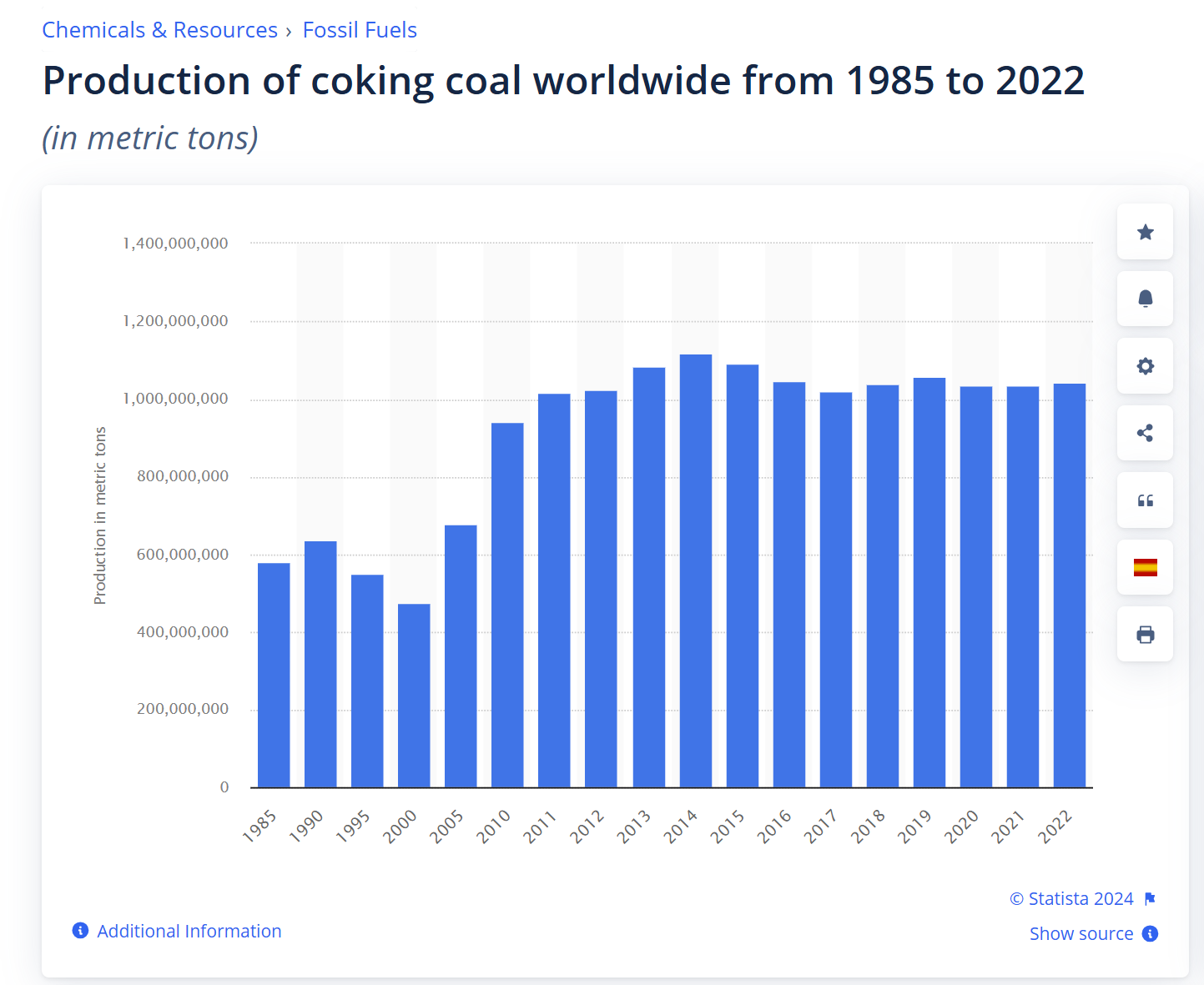

Starting with what I think is the easiest to address: met coal supply. As shown in the chart below, after peaking in 2014, coking coal production declined until 2017 and has remained mostly stable since then.

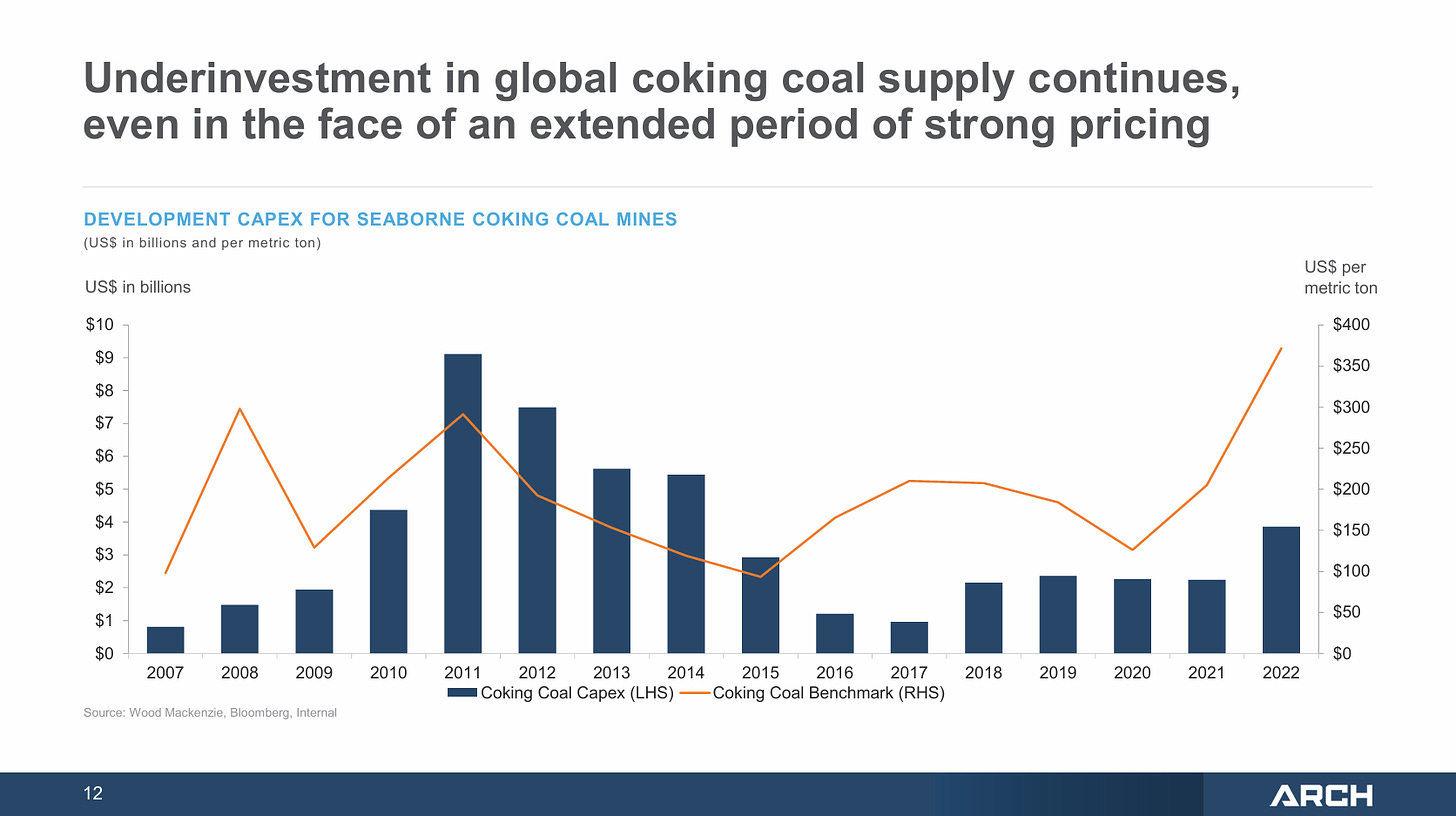

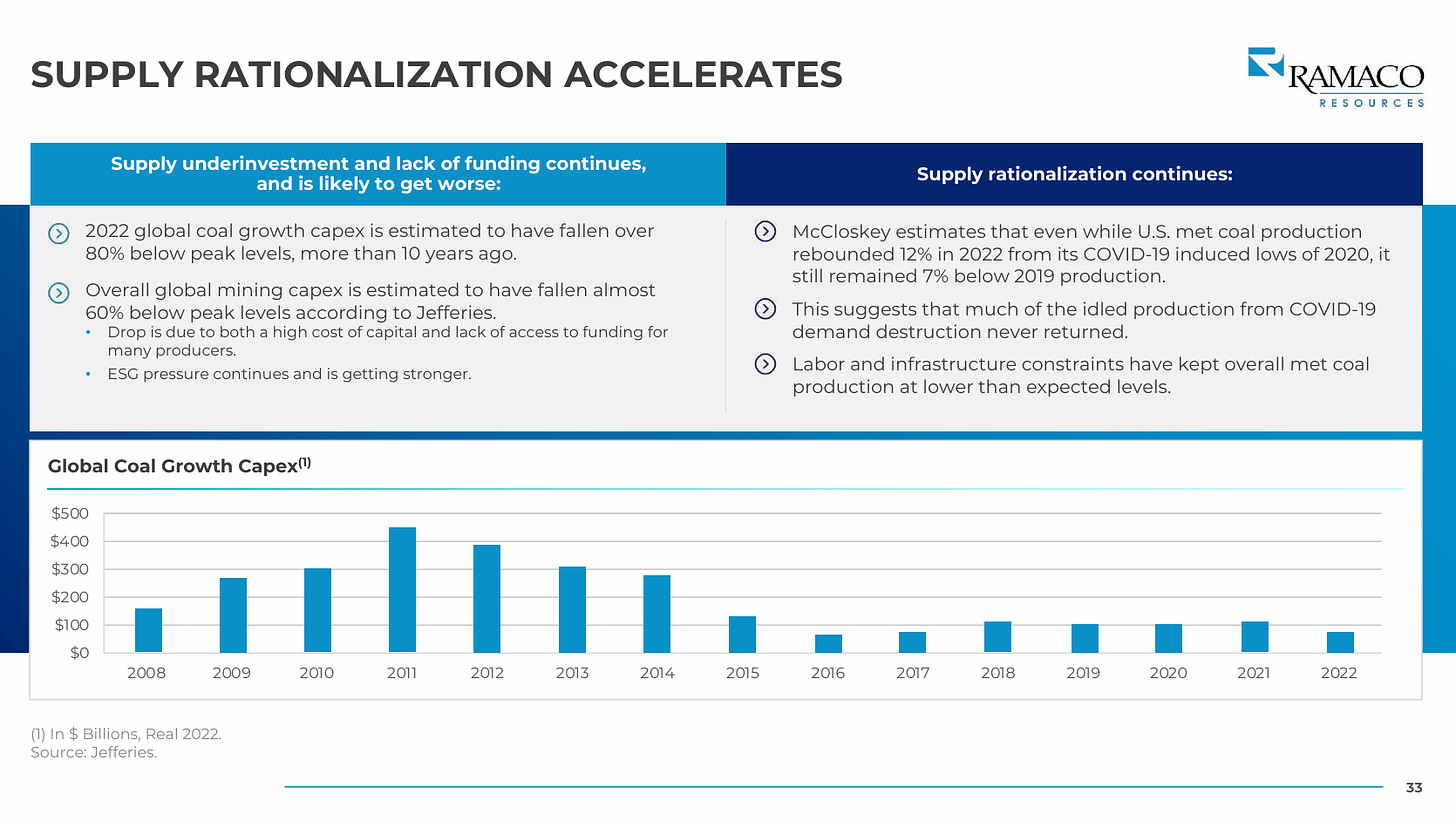

A look at the global met coal mine development capital expenditures helps explain this trend. As shown in the slides from ARCH and METC below, development capex has been steadily dropping since peaking in 2011 and is currently over 50% down from peak levels.

What has driven this significant decrease in capex for new met coal asset development? It probably won't surprise you to learn that the key factor has been ESG and decarbonization trends, which have led to regulatory pressures for new mine approvals and made projects increasingly difficult to finance. I would refer you to commentary from publicly listed met coal producers—see the quote from ARCH’s Q3’23 conference call below.

As we've noted repeatedly, the global investment in new and existing mine capacity has been extremely muted the last several years due to increasing development costs, mining regulatory pressures and a host of other ESG-related concerns, and we see no evidence of that changing in the near future. Indeed, we suspect that even a modest improvement in global macroeconomic conditions could drive additional supply tightness well into the future.

<…>

There is no question that the current market is under -- the supply is very tight. The underinvestment in the coal sector is really rare in its head.

To illustrate these dynamics, let’s consider the example of Australia, the by far largest met coal exporter globally, where new mine development has been stalling (e.g., see here). As detailed in this Australian coal mine tracker, since early 2022, the Australian government has approved only four new mines or expansions of existing projects. These four new mines/expansions are projected to produce 55m tons over their lifetimes compared to the 157m tons Australia exported during FY23 alone. Thus, the incremental supply that has come online in recent years is, to say the least, pretty insignificant.

To highlight the difficulty of obtaining new mine approvals and funding, I would direct you to this article from last year, which includes supporting statements from management teams of several Australian met coal producers (see quotes below). I should note that these statements were made in the context of a potential bidding war for BHP’s coking coal assets, reflecting the dire outlook for new supply coming online.

Coronado Global Resources’ CFO:

It is difficult to see how the demand growth will be met by supply growth, given the limited approvals for new mines in the high-quality met coal regions of Australia and North America,

Yancoal Australia’s CEO:

It's worth considering just how difficult it has been to get new mine approvals and funding for those new mines in recent years. Coal prices would not have reached the levels we've seen in 2022 if new supply had been incentivized.

Similarly, last year, the Australian government highlighted that met coal producers have been facing significant financing difficulties, with banks pivoting away from financing met coal producers. See the excerpt from the Australian quarterly resources and energy review below:

Metallurgical and thermal coal producers face growing constraints on availability of finance. Banks have increasingly sought to pivot away from all forms of coal in favor of renewables and related commodities. Hopes among some producers that metallurgical coal would be unaffected have not been entirely borne out. This is likely to place some further constraint on metallurgical coal investment over coming years.

Now, there is admittedly a large pipeline of proposed new coal projects or existing project expansions in Australia (32, including both thermal and met coal projects, according to this coal mine tracker). However, I would refer you to a number of withdrawn or rejected coal project proposals, including for met coal mines, that have been withdrawn or rejected in recent years (see here). This, coupled with the slow pace of approvals thus far, suggests that supply is unlikely to grow significantly in the coming years.

So, to sum up, the current situation is that there is a lack of new supply coming online from the world’s dominant met coal exporter, Australia, and given decarbonization trends, this seems unlikely to change significantly in the foreseeable future.

The situation is similar in other major met coal exporters. In the US, the third-largest met coal exporter, no significant supply is projected to come online in the coming years. As detailed in this coal mine tracker, only three new met coal projects are currently pending in the US. The largest of these projects, the Blue Creek mine, is expected to have a production capacity of approximately 5m tons annually. Needless to say, this does not move the needle considering total export volumes globally (300m+ tons).

As for Canada, the total incremental supply expected to come online in the coming years is c. 15m tons (according to this coal mine tracker). While this might be considered a sizable incremental supply, note that this includes a 10m ton/year Fording River expansion that will mostly extend the lifespan of the existing mine.

Meanwhile, another large exporter, Russia, also boasts only a handful of new met coal projects or expansions (see here).

So, what we have here is a lack of any significant supply coming from the four largest met coal exporters globally in the coming years.

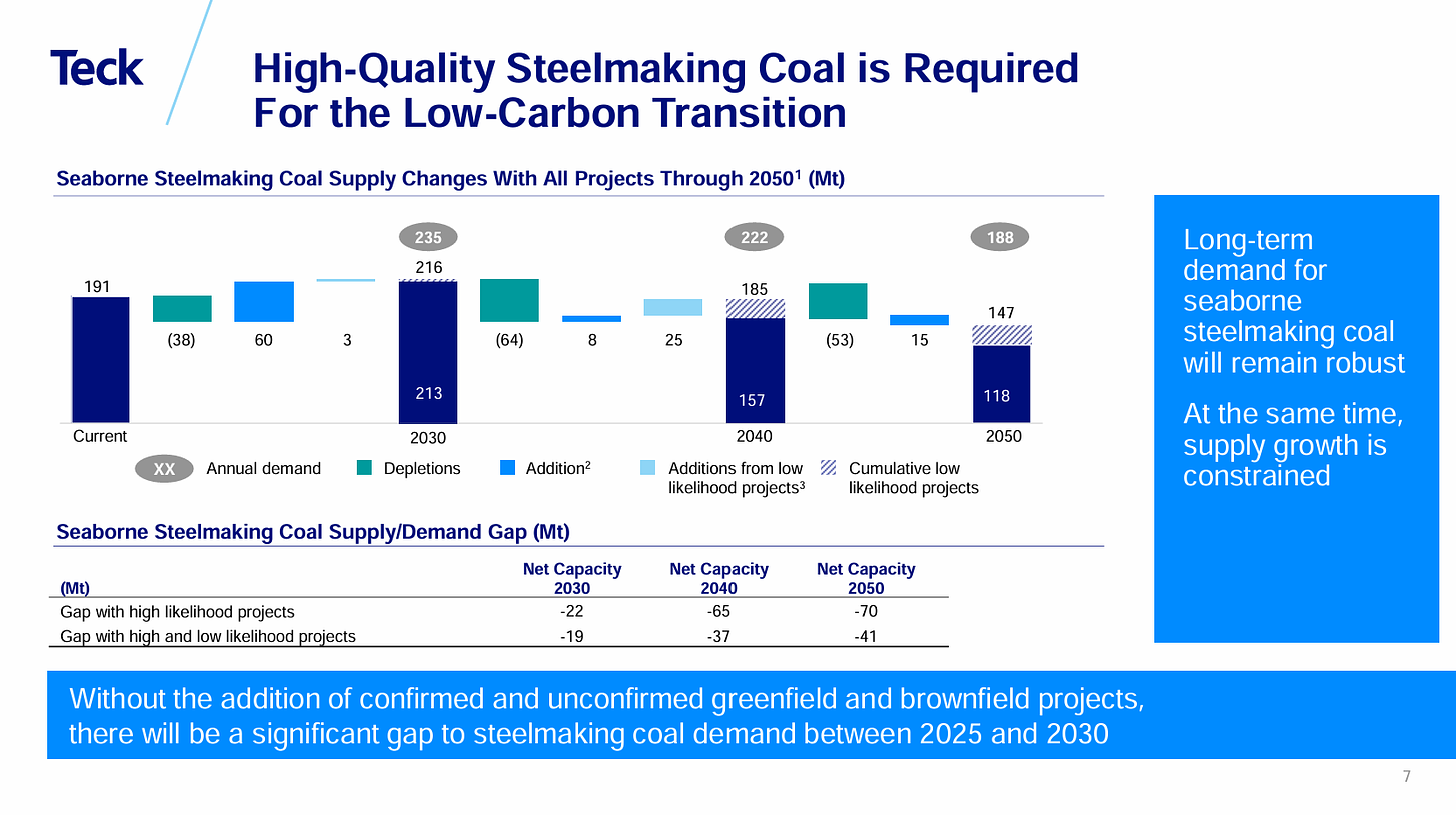

Given these points, coupled with the depletion of existing assets, I think it is safe to conclude that supply is unlikely to grow materially in the coming years. Not surprisingly, then, Wood Mackenzie projects stable or declining met coal supply (see the excerpt below). Meanwhile, Teck Resources has highlighted that supply is expected to decline during 2030-2050 even when accounting for low-likelihood projects (see the slide below; low-likelihood projects are those that would require higher met coal prices to be economically viable).

Longer term, the availability of premium hard-coking coal (PHCC) is a major concern to international steel makers. Wood Mackenzie’s coal supply asset data suggests a net drop in premium low volatile HCC supply by 2027, compared to 2023. Premium mid-volatile HCCs can see net growth but we estimate it will be limited to 15-16 Mt above 2023 levels in the long term. This trend suggests steel mills will have to adjust coke blends over time, relying more on lower quality metallurgical coals, and will likely see a growing price differential between premium coals. India is focusing heavily on stamp-charged coke ovens, a strategically sensible move widening the quality of feed coals that can be used in coke-making.

Steel Demand

Let’s now turn to another key factor impacting the met coal industry: the demand for steel.

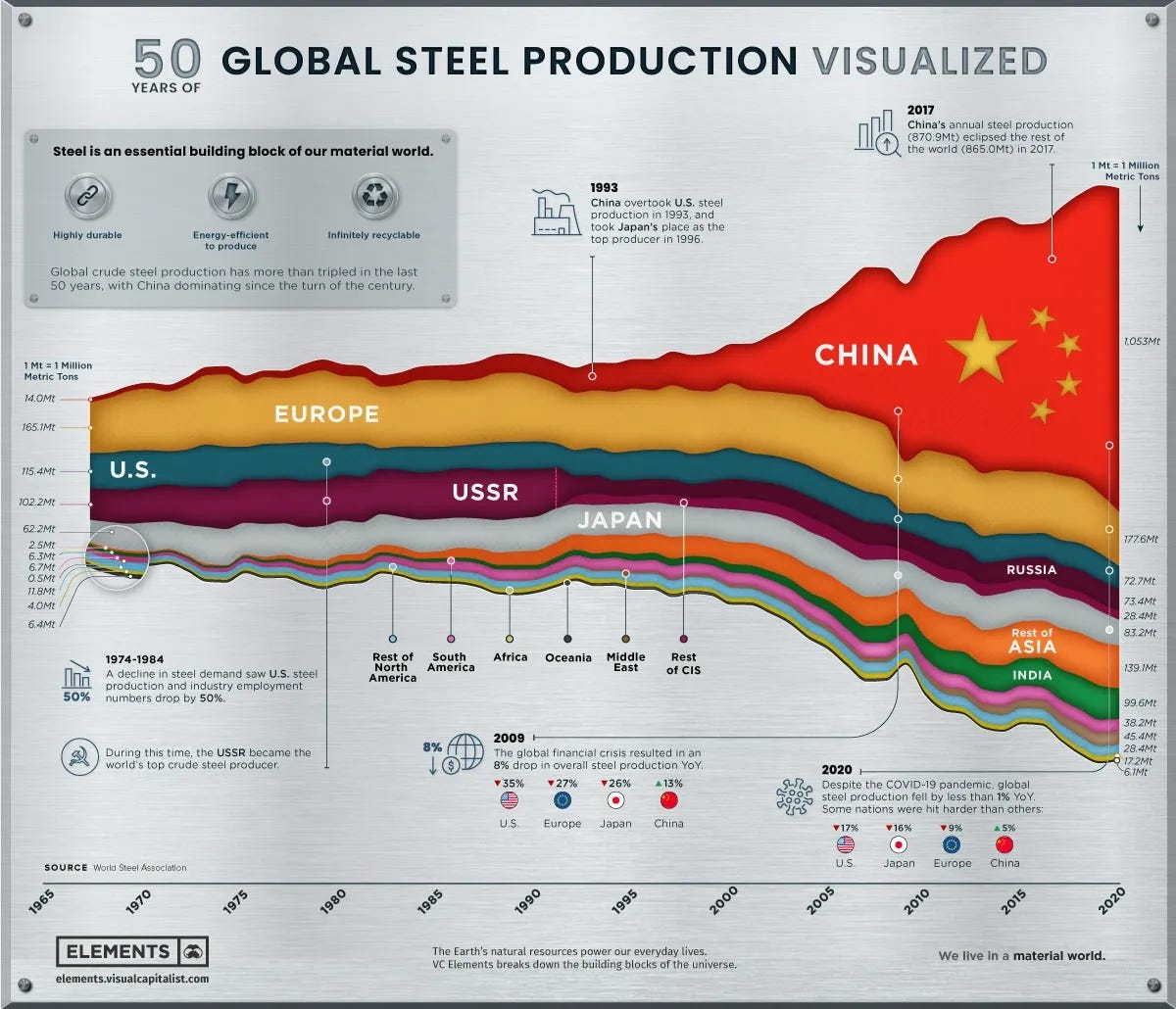

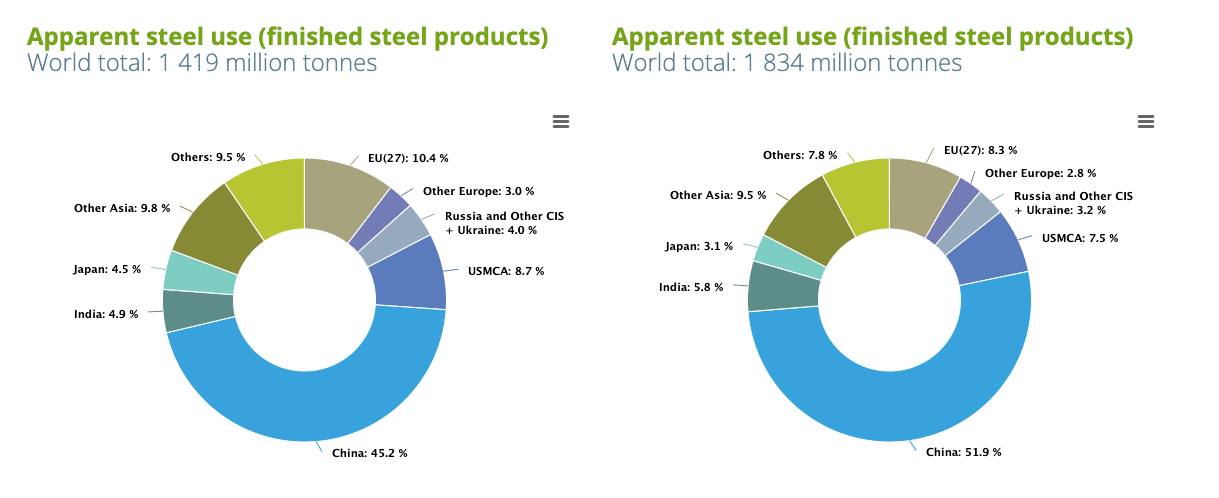

Steel demand has risen significantly over recent decades, driven largely by China’s urbanization (see the chart below, note that steel production is a good proxy for steel use/demand as steel is mostly consumed in the country where it is produced). Strong and growing Chinese demand has propelled the country’s share of global steel demand to a massive 52% as of 2021 (up from 45% in 2011; see another chart below). Clearly, China is the 900-pound gorilla in the steel industry, so any discussion of global steel demand must revolve around it.

As most investors are aware, the Chinese economy has been suffering from a macroeconomic slowdown, driven partially by weakness in the property sector. Weaker domestic consumer demand has led to China dumping its steel onto world markets, resulting in lower steel and met coal prices (see the quote from a recent ARCH conference call below).

And turning to the met coal markets, both the U.S. and global met coal indices have continued to fall meaningfully throughout the year. This drop has, of course, negatively impacted our price realizations across the board. The biggest reason was simply muted overall global economic and steel demand. This was coupled with China's slower internal growth and overproduction of steel and a corresponding dumping of the steel in the world markets. It's tough to expect strong met coal pricing when the world is awash in cheap steel.

So, the Chinese macroeconomic slowdown clearly represents a real risk to global steel demand (and, thus, met coal demand and prices) in the coming years.

How do we assess this risk? I think there are two key questions worth addressing in this context:

How sizable of a decline can we expect in China’s steel demand going forward?

Will growing steel demand from other countries offset the potential weakening Chinese consumption?

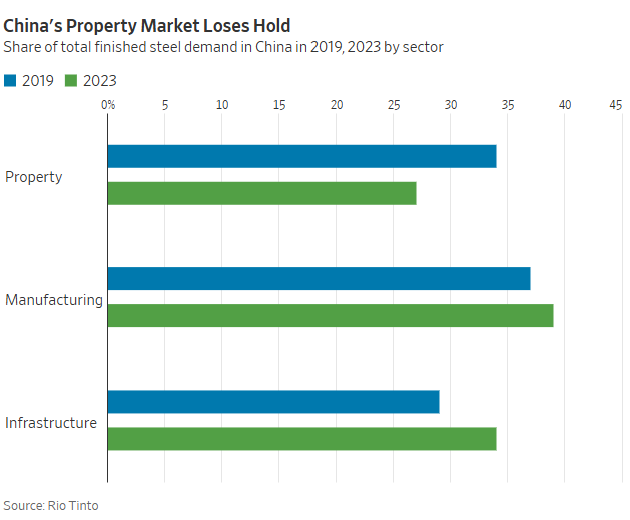

Starting with the first question: I will note upfront that I do not have a high-conviction view or visibility on future Chinese demand for steel. That said, I would note that thus far, the impact of China’s slowdown on steel production has been limited. As highlighted here and here, demand for steel has held up well, driven by solid demand from the manufacturing and infrastructure sectors (also see the chart below). For instance, World Steel Association data shows that pig iron (an intermediate good in steel production, obtained after mixing coke with iron ore in a blast furnace) production fell by an insignificant 3.6% in H1 2024. This contrasts with the 10% and 20% declines in Chinese property investment and property sales during the first five months of 2024. What this indicates is that weakening demand from the property sector has thus far been mostly offset by growing steel consumption in the manufacturing and infrastructure sectors.

There is admittedly a risk of a full-blown financial crisis in China, with the manufacturing and infrastructure sectors potentially slowing down. In this scenario, Chinese demand for steel would likely decline markedly. However, while this is certainly a possibility, I’d refer you to the massive investments China has been making into energy infrastructure (e.g., see here), which obviously requires steel. So, given the dynamics of Chinese steel demand thus far and government spending on infrastructure, I am inclined to think that China’s steel demand is unlikely to fall off a cliff in the coming years. Industry forecasts support this view: according to the World Steel Association, Chinese steel demand is currently forecasted to be flat in 2024 and to decline only insignificantly, by 1%, in 2025.

This brings me to the second question: will growing steel demand from other countries offset the potential weakening Chinese consumption? Again, making such forecasts with high conviction is clearly difficult. Nonetheless, what suggests that steel demand is likely to remain robust in developed markets are the massive ongoing investments in infrastructure (e.g., renewable energy, data centers) and defense sectors across developed countries. For example, I’d point to large government spending programs approved in the U.S., including the $1.2tn Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the CHIPS Act. In Europe, I’d illustrate this with the EU’s Global Gateway initiative, which aims to spend €300bn on energy, transportation, and digital sectors during 2021-2027 (also see here).

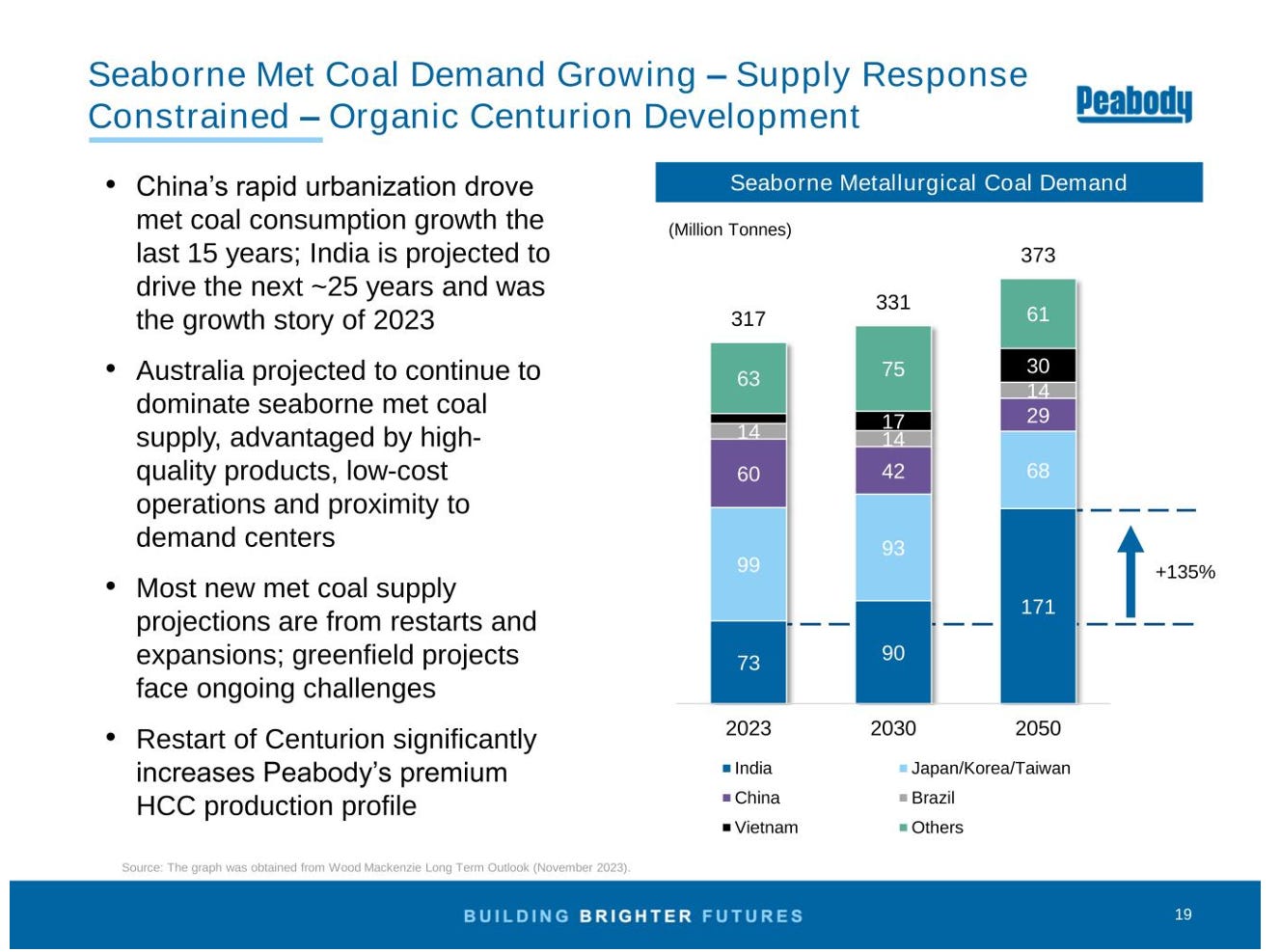

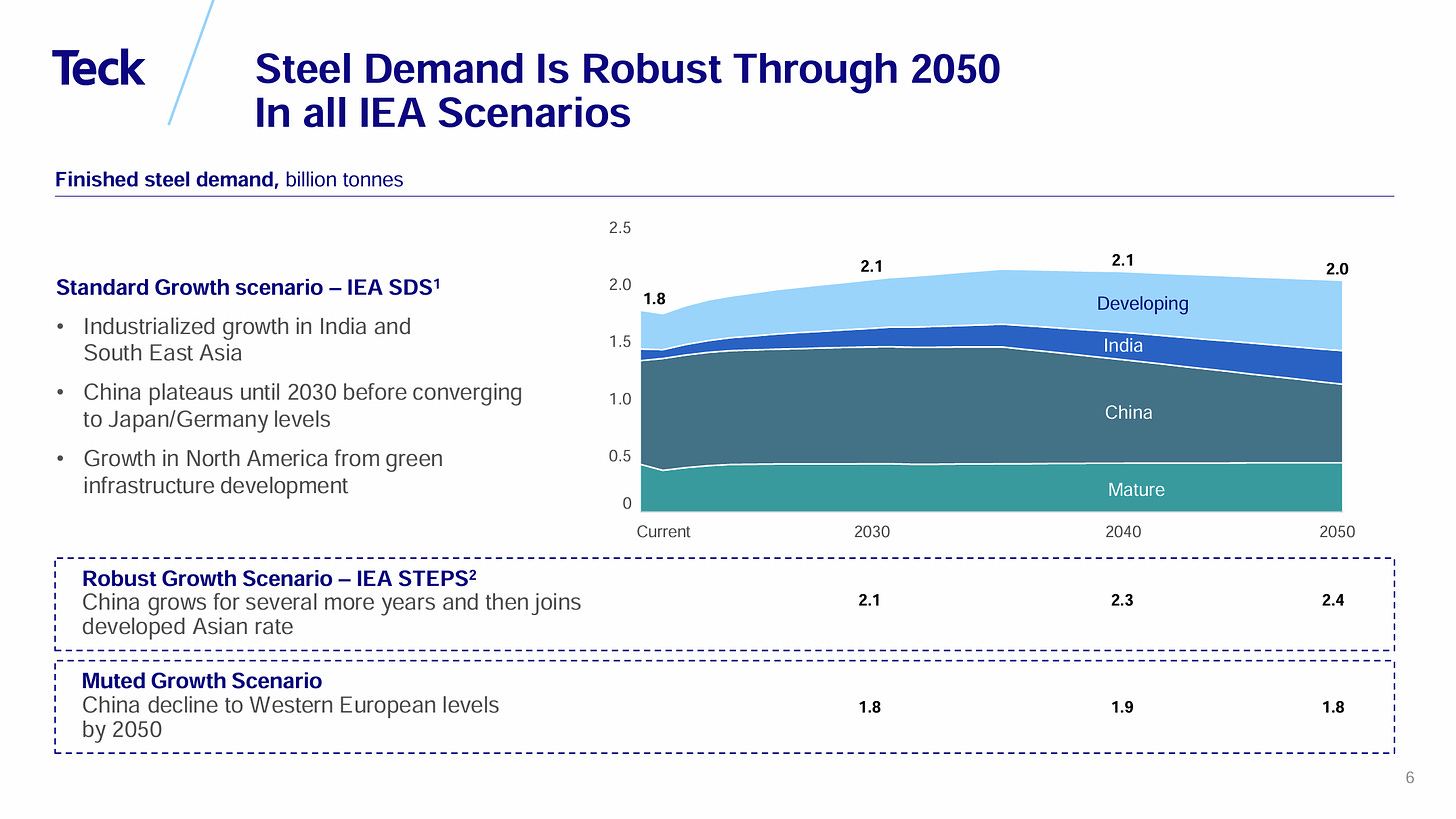

And I have not yet mentioned a key driver for global steel demand growth: India. If you look at the investor presentations from any met coal producers, you will most likely come across India as the expected key growth driver for steel demand (for example, see slides from BTU and AMR below). Massive steel demand from India is expected to be driven by ongoing urbanization, with a vast number of individuals entering the middle class. According to the IEA, met coal consumption in India grew by 10% and 12% in 2022 and 2023, respectively, and is forecast to grow at an 8% clip during 2023-2026 (see here, p. 115). While I am unable to verify these projections, given the low urbanization rate of 36% as of 2023 (compared to 66% for China), the growth runway for steel demand seems immense. As an illustration of ongoing/expected urbanization, I’d note this tweet highlighting Tata Steel (India’s largest steel producer) plans to double its steel production in the country by 2030.

Will the demand from India help offset the expected demand slowdown from China? A recent IEA report suggests that the global met coal consumption is expected to remain steady through 2026, with the decline in Chinese consumption largely offset by incremental demand from India. Other sets of data similarly confirm that demand from India would roughly offset the decline in steel demand from China in the coming decades (see another chart below).

Again, I have limited knowledge and information to support or refute this forecast. Nonetheless, here I would like to mention the interest of Mohnish Pabrai in met coal producers. Given Pabrai’s knowledge of/familiarity with the Indian economy, I would suggest that his investment in met coal producers might be partially explained by his bullishness on India. Considering Mohnish’s investment track record, this lends some additional confidence that steel demand in India will drive global steel demand in the coming years.

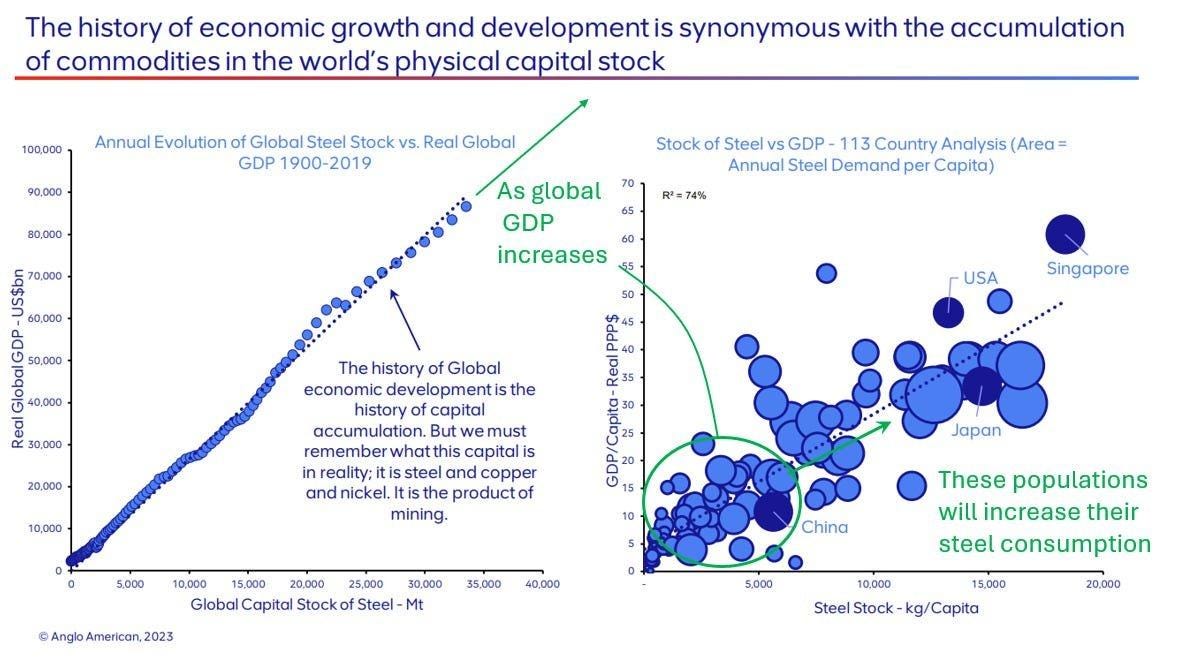

As for other developing countries, I would simply point you to the chart from Matt Warder below, highlighting the strong correlation between GDP per capita and steel consumption per capita. This indicates a substantial growth runway for global steel consumption in the long term.

So, to sum up the discussion of steel demand, I would like to state that while short-term demand fluctuations are certainly possible, the longer-term outlook for steel consumption appears slightly negative at worst and positive at best.

Electric Arc Furnaces

This brings me to the third aspect: the competition for met coal coming from alternative steel production methods, namely steelmaking in electric arc furnaces (EAFs).

For a very quick background, steel production using EAFs involves melting scrap metal and refining it into new steel in mini-mills (i.e., steelmaking complexes, contrasts with integrated mills in traditional steelmaking).

While traditional blast furnaces remain the dominant steel production method globally (c. 70% of steel production), EAFs have been gaining market share in developed economies due to their significantly lower CO2 emissions. As of 2021, EAFs (with scrap metal as the primary input) accounted for 70% of steel production in the U.S. and about 50% in Europe. Thus, we can clearly see that developed countries have been shifting toward steel production using EAFs. This raises the risk that other countries might also significantly shift to this steel production method at the expense of traditional blast furnaces.

However, this seems highly unlikely to occur, at least over the coming decades, given EAFs disadvantages compared to traditional blast furnaces. EAFs have higher production costs compared to blast furnaces (see here and here). On top of that, EAFs also require significant amounts of scrap metal as well as access to cheap and reliable electricity. Another aspect is that recycled steel is of lower quality than virgin steel, as it mostly comes from automotive scrap, which contains copper impurities (see here). This results in the superior strength and durability of virgin steel. Given these arguments, it is reasonable to conclude that traditional blast furnaces are likely to remain dominant in developing countries.

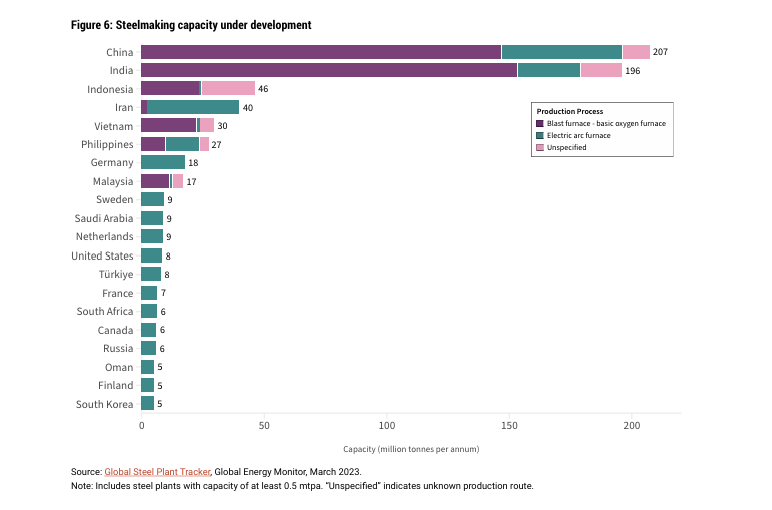

And the actions of major steel producers reflect this. Let’s consider the two largest met coal consumers and importers, India and China. The majority of new production capacity in these countries will comprise traditional blast furnaces (see the slide below). While both countries have announced plans to increase the share of steel production using EAFs, this share is targeted at a meager <20% in China (up from 10% currently) and 30% in India (up from 8% as of 2021) by 2030.

The same dynamics can be observed in other steel-producing countries. Wood Mackenzie projects that 85% of incremental steel production capacity in Southeast Asia through 2030 will come from blast furnaces (also see here).

So, I think it is safe to conclude that the share of EAFs in steel production globally is unlikely to reach the levels seen in the U.S. and Europe over the coming decades. As an indication of this, Wood Mackenzie estimates that by 2050, 50% of global steel production will come from EAFs. This strongly suggests that the risk of met coal obsolescence in the near/medium-term is minimal.

Conclusion

This post provides a high-level overview of the investment case for met coal. My key takeaway is that the general outlook for met coal producers over the coming years is neutral to positive, given tight supply and likely stable or growing demand. While met coal may eventually become a declining industry in the long term, that scenario still appears to be very far off.

This concludes the first part of the series on the met coal industry. I plan to share my thoughts on what makes met coal an interesting investment opportunity at this moment in an article in the coming weeks.

Great article, thank you!

Germany is considering the reintroduction of coal-fired power plants to support its winter power supply. This decision comes as part of the country's efforts to ensure energy security in the face of ongoing challenges.

1. The German government has approved a plan to bring some shuttered coal-fired power plants back online.

2. This move is primarily in response to the reduced imports of Russian natural gas following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

3. Several coal-fired units operated by energy companies RWE and LEAG at their Niederaußem, Neurath, and Jaenschwalde power plants will be temporarily reactivated.

4. The reactivation of coal plants is seen as a measure to provide more security for Germany's electricity supply.

5. This decision comes despite Germany's commitment to phase out all coal-fired generation by 2030.

6. In 2023, Germany's coal power production dropped to its lowest level in 60 years, with lignite power production falling to the lowest level since 1963 and hard coal power production dropping to the lowest level since 1955.

7. The German government maintains that it does not plan to introduce a new law to ensure a coal exit earlier than 2038, leaving the possibility of a market-driven phase-out before then.

This reintroduction of coal-fired power plants maybe a temporary measure to address immediate energy security concerns, but the result is tha coal is back in tge equation.